Master Collection 2: animal studies

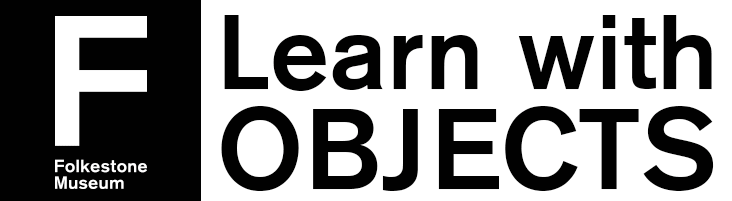

This pencil drawing of The so-called Temple of Vesta, Rome was sketched by the English artist Samuel Prout (1783-1852).

In the foreground are several oxen (large cattle) lying down for a rest.

The wheels belong to wooden carts pulled by the oxen. You can see oxen pulling a wooden cart in the drawing by William Collins.

This area of Rome was the site of the ancient Forum Boarium or cattle market.

The impressive circular building in the foreground is a small Roman temple known as the Temple of Vesta. However, we don’t actually know which Roman god or goddess it was dedicated to.

The temple consists of a circular wall surrounded by fluted columns, which have elaborate Corinthian capitals on top. In the Middle Ages it became a church and a tile roof was added. The church was Santo Stefano delle Carrozze, or Saint Stephen of the Carriages, later Santa Maria del Sole, or Saint Mary’s of the Sunshine.

On the right is a rectangular Roman building. This is the so-called Temple of Fortuna Virilis, more probably dedicated to Portunus, the Roman god of harbours. In 872 it was consecrated as Santa Maria Egiziaca, or Saint Mary Egyptian.

In the distance on the right is a medieval building incorporating Roman half-columns. This is the Casa dei Crescenzi, erroneously called the House of Cola [short for Nicola] di Rienzo.

Look closely.

- Can you spot all the washing hanging out to dry?

- Can you see Prout’s inscription below his drawing, ‘Maison de [House of] Nicola de Rienzi’?

Nicola Gabrini, known as Cola di Rienzo or Rienzi (1313-1354), was a popular revolutionary leader, who wanted to revive the fortunes of Rome and unite Italy. He was the subject of a poem by Petrarch, his contemporary, and of numerous novels, plays and operas in the 19th century when the new Kingdom of Italy was formed.

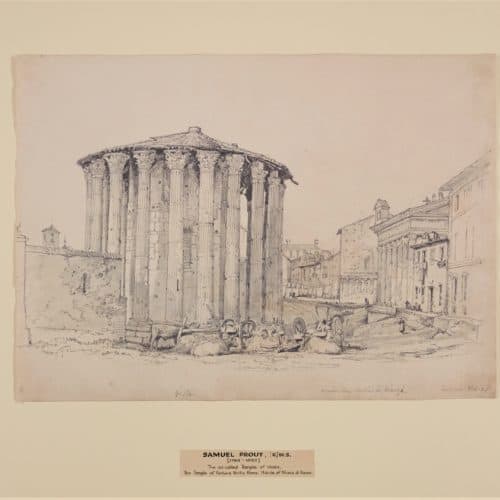

A Roman Oxcart by William Collins RA (1788-1847).

Drawn in pencil, pen, black ink and watercolour heightened with white, on light brown paper.

Two powerful oxen are pulling the cart. They have cloven hooves and huge horns similar to the ancient cattle breed, the aurochs.

The cart is pulled by a draw bar: can you see the wooden bar between the oxen? They are harnessed to the bar. The cart driver holds reins that go round the bar and also the horn of one ox. This is the leading ox. The driver can make the ox, and therefore the cart, move to the right or left by pulling the reins.

- Can you spot the decorative red white and blue tassels above the oxen’s nose?

An open-sided cart like this was usually used to carry hay (cut and dried grass) or straw (cut and dried stalks from grain) for cattle feed or other purposes.

The cart wheels were made by wheelwrights. The large wheels usually had an outer iron band for durability, made by blacksmiths. Cart wheels like these would be usable for decades, even centuries. Their design is unchanged since Roman times.

William Collins, who drew this oxcart, was a painter of landscape and everyday life or ‘genre’ pictures.

He came to Rome with his family in 1837. His novelist son, Wilkie Collins (1824-1889), later wrote in a memoir of his father that he was never without a sketchbook: ‘wherever he went – whether to a gallery of pictures, or a cardinal’s levee, to a ceremony in a church, or a picnic in the garden of a palace – his eye was ever observant, and his hand ever ready, as he passed through the streets’. (W. Collins, Memoirs of the Life of William Collins, Esq., R.A., London, 1848).

The Collins family had left England for Italy in September 1836, but were delayed in Nice for six weeks because of a cholera epidemic and severe quarantine restrictions in Italy. They left in December and headed for Genoa, then to Pisa and Florence, arriving in January 1837 at Rome. There Collins studied the frescoes of Raphael, Michelangelo and Domenichino, as well as buildings, city views and people.

From Rome the Collins family travelled to Naples. They had planned to stay there for a while but due to an outbreak of cholera they moved to Sorrento. After an excursion to Amalfi, Collins was taken ill. Suffering from rheumatic fever, he left with his family in October for Ischia, to see if the sulphur baths there would help. When he felt better, the family travelled back to Naples and again to Rome, then to Assisi, Florence, Bologna, Parma, Verona, Padua and Venice, where they stayed a month. They returned to England via Innsbruck, Saltzburg, Munich, the Rhine and Rotterdam, reaching London in August 1838.

Thomas Man Bridge, who owned this drawing, visited many of the same places as the Collins family on his continental tours in 1839 and 1843-1844. When William Collins sketches and paintings were auctioned after his death, at Christie’s, London, in May-June 1847, Bridge bought many of the works. They would have been a reminder of what Bridge had seen on his own travels with his sister Frances and future wife Julia.

His wife predeceased him and the collection that Bridge had formed passed to Frances, then to her step-daughter Mrs Amy Master, who gave it to Folkestone Museum in memory of Frances.

Wilkie Collins, the older son of William Collins and his wife Harriet (a teacher and writer), was baptised William Wilkie after his father and godfather, the painter Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841).

Sir David Wilkie was a close friend of William Collins, whom he encouraged to travel to Italy. Wilkie died in 1841 of suspected cholera contracted in Malta. As a child, his godson met the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, as well as many artists. His father’s artist friends included his maternal aunt, Mrs Margaret Carpenter (1793-1872), the most successful woman painter of her time.

Wilkie Collins showed some aptitude for painting but preferred writing. After publishing the posthumous memoir of his father, Collins met Charles Dickens, who encouraged him to write. The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868) are his best-known novels.

His younger brother, Charles Alston Collins (1828-1873), was named in turn after his godfather, the American history painter Washington Allston (1779-1843). Charles studied in the Royal Academy Schools, where he became a close friend of William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

When Hunt and Millais with other friends formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Collins was not elected, but he shared their interests and meticulous painting style.

Collins suffered from great anxiety and depression, which hampered his painting. In 1857 he turned to writing, including travel accounts and novels. He married the youngest daughter of Charles Dickens, Kate, in 1860.

Saint George and the Dragon by an unknown artist. Black chalk, pen and grey ink, grey wash on paper.

The man on horseback is Saint George. He is recognisable as a soldier on horseback fighting a dragon.

The dragon has one tail. The second curly tail belongs to the horse!

- How has the artist made the two tails look different?

The dragon has clawed feet. There are four claws clearly visible on one foot, ending in sharp talons. The dragon also has wings.

- Can you find one?

Saint George is a legendary warrior and martyr. He is said to have been born in Cappadocia, in Asia Minor, and to have died at Lydda, in Palestine, at the end of the 3rd century AD.

In the legend, St George rescues a princess from a venom-spewing dragon. He later beheads it with his sword, after the people of her city promise to become Christians.

The earliest record of St George slaying a dragon dates from the 11th century. The story was brought back to Britain by the Crusaders and was a popular subject of medieval and Renaissance writers and artists.

He was especially venerated in the Greek church but did not become popular in the West until the 13th century.

Dragons were symbols of evil and paganism to early Christians. A heathen country converted to Christianity could therefore be symbolised as a dragon slayed. This may be the origin of the story of Saint George.

The Greek myth of Perseus slaying a monster may also have been a story source. Saint George, just like Perseus, is said to have fought a dragon by a seashore, outside the walls of a city, to rescue a maiden being offered as a sacrifice.

Saint George is generally depicted dressed in armour and riding a horse, usually white for purity. He brandishes a sword. Often his broken lance is shown lying on the ground or stabbed into the dragon.

The inscription top left on the drawing refers to the artist Luca Cambiaso (1527-1588). Someone in the past has attributed this drawing to Cambiaso, a painter from Genoa who went to work for the court of King Philip II of Spain. The art historian Mary Newcome Schleier suggested it was more like the work of Nicolosio Granello (about 1500-1560), another artist from Genoa.

Did you know?

Saint George is the patron saint of England, Ethiopia, Georgia, Malta, the Palestinian territories and Portugal. He was made patron saint of England in 1222. His feast is celebrated on 23 April.

Studies of a Swan by Alexandre-François Desportes (1661-1743).

Black, red and white chalk on light-brown paper.

The swan has white feathers and an orange beak. It’s resting but has a powerful wing partly raised.

The French artist Desportes has written himself helpful notes about colour. Below the swan’s foot he has written in French les pates noire grisatre, meaning the feet greyish black. On the top left he has written about the colour of the swan’s head and neck.

Desportes was a painter who also designed tapestries. He had a large studio at the Sèvres factory in France. Colour notes like these helped his assistants recreate images of animals with vivid realism.

His speciality was scenes of hunting or of dogs and dead game. He is known to have accompanied the French king Louis XIV on hunts. Desportes also studied animals and birds in the royal gardens and menagerie, including a tiger.

The animal on the stamp is a boar. It is the family heraldic animal of the collector Thomas Man Bridge, whose initials T M B appear below the boar. Art collectors often marked their drawings and prints to prove ownership. The marks became part of an object’s history or ‘provenance’ – the story of who had owned them.

Did you know?

Swans are royal birds. In England swans are owned by the Queen and it is illegal to kill them.

Studies of Deer with a City beyond.

Attributed to Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625). Black lead, pen and brown ink on paper.

The animals in this drawing are deer.

They are grazing. The artist has observed and sketched lots of different behaviours of deer. One has a mouthful of grass; several others are nibbling grass; one is licking its foot. Most are standing and three are lying down.

By sketching this variety of positions, the artist had a wide range to choose from when he later came to make a painting in his studio.

In the background of the drawing is a city. A large cathedral on the left is surrounded by city walls with turrets. There are spires of other churches behind walls on the right. People are taking a stroll.

Between the city and the deer are large railings. These deer are likely owned by royalty or nobles who hunted them.

Jan the Younger was a Flemish painter who lived in Antwerp, a famous port city on the River Scheldt, which is now part of Belgium. He specialised in landscapes (pictures of the countryside).

In the 1600s Antwerp was the home of many famous artists including Rubens.