WW2 9: evacuation

This is an official letter sent out to all parents and schools in Folkestone in January 1939 to advise them of the Government’s plans in the event of war. It’s signed by the Mayor of Folkestone at the time, Mr George Albert Gurr.

Here is an extract from the evacuation letter sent to parents in Folkestone during the second wave of evacuation in 1940:

As you have no doubt heard from the Minister of Health’s broadcast on Sunday night and from the newspapers, the Government have decided that parents of school children living in the town are to have the opportunity of sending their children away to a safer district. The evacuation of school children will begin on Sunday next, 2nd June […] Please remember (1) that only those children whose parents register them at the school will be taken. (2) That when the children have been taken to safer areas, parents will be expected to leave them there until the Government decides that it is safe for them to return. The children will go to places in the Midlands and Wales that the Government consider are safer than this town. You are free to decide for yourself whether your child should be sent away to a safer area or not. It is hoped that parents will not decide to keep their children in this town without thinking very seriously whether such a decision is in the best interests of the children themselves.

This must have been a very hard decision for parents to have to make, especially not knowing where their children were going to be sent to and for how long they would be separated.

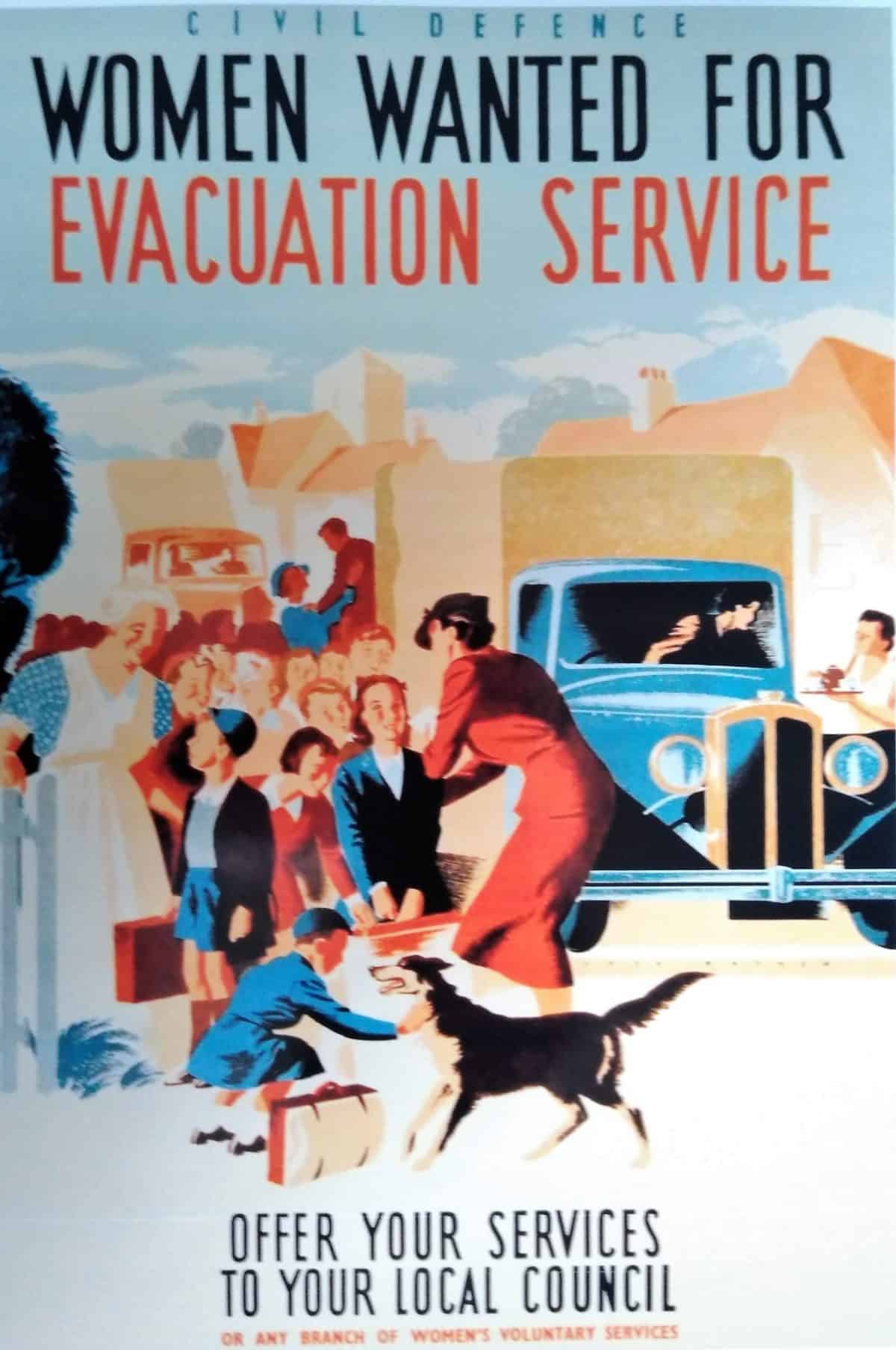

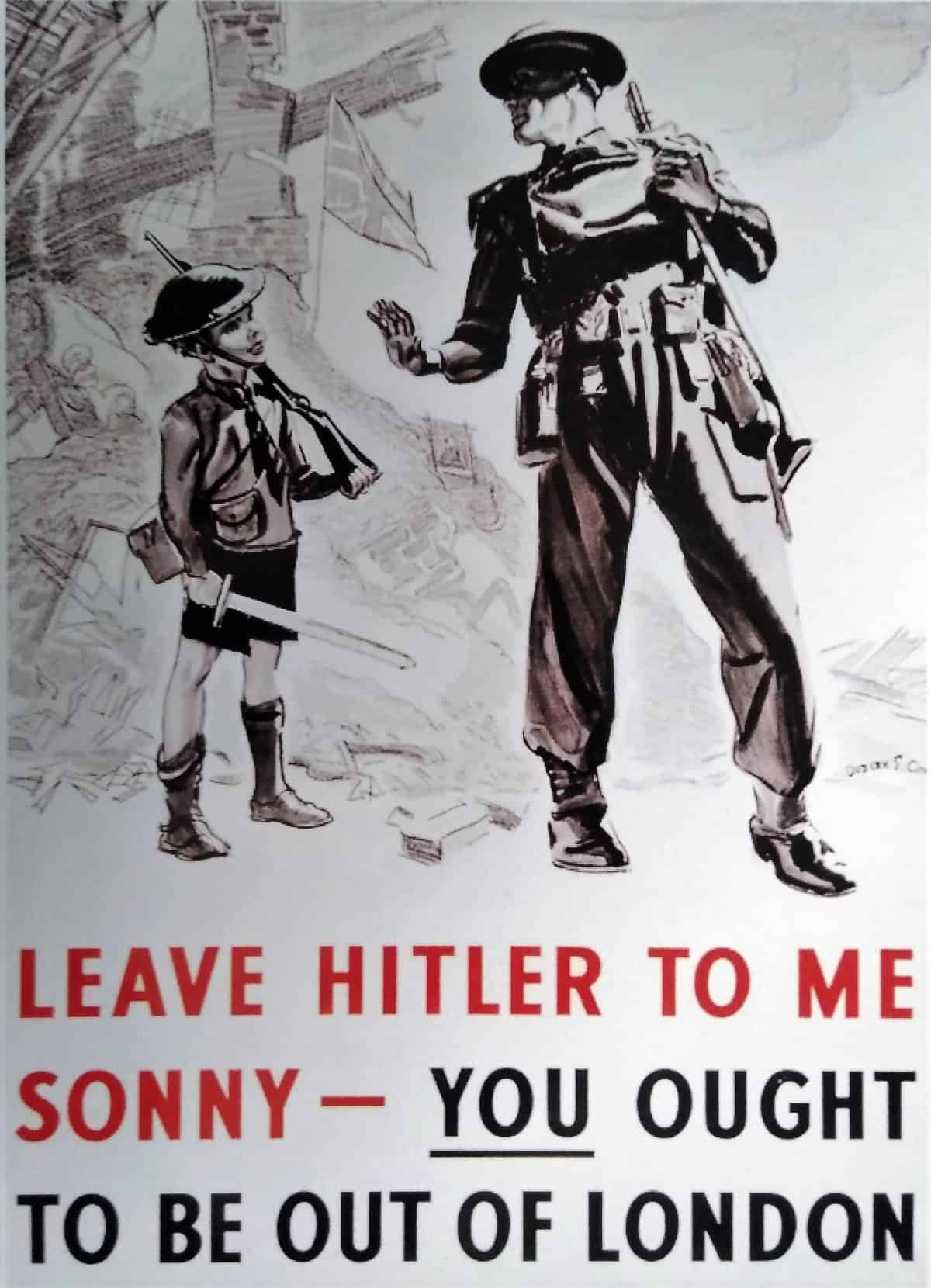

These are Government propaganda posters from 1939 and 1940.

The first is to recruit female volunteers to accompany the evacuees.

The second is urging parents to take part in the evacuation scheme.

Fascinating Fact

At first, Folkestone was thought to be a safe place and children from London were evacuated to the town. However, after the fall of France in 1940, they joined the Folkestone children being evacuated to the countryside.

This photo shows a little girl aged about 5 or 6. She is asleep in a pram clutching her teddy bear.

Many children from Folkestone were evacuated to Wales, to the villages around Abergavenny and Merthyr Tydfil. Here’s an extract from the memories of a Folkestone evacuee who attended Stella Maris school:

We were taken to the railway station where there was a long train waiting. We said goodbye to our Mums and Dads. Everyone was crying. We all tried to be brave and hoped to be all together again soon. As the train left everybody was waving. There were over 800 children on the train from all the schools in Folkestone and Dover. We sat down and cried but our teachers encouraged us to sing and we did.

For many children the journey to the countryside took many hours, as evacuee trains were often stopped or diverted, to give priority to military supplies and troop trains.

One Folkestone refugee remembers the journey very well:

It was about 10am and it was very hot. We were told we would be stopping for refreshments and would reach Merthyr Tydfil by 2pm. It was a terrible journey. The sun was too hot and there were air raids. The train had to stop in case the German plane bombed the train. I was very sick and we didn’t reach Merthyr Tydfil until 5.30pm.

Children were only allowed to take one suitcase, containing a change of underclothes, night clothes, plimsolls, socks, toothbrush, comb, soap, face cloth, handkerchief and a warm coat. Children also had to carry their face mask in its box. Some children took one toy with them.

What toy would you take with you if you were an evacuee?

When children arrived in the countryside they were usually walked to a local village hall, where they were assigned to families. Sometimes local families could pick which child they wanted. This meant that some brothers and sisters were separated into different households.

One Folkestone evacuee remembered being separated from his brothers and sisters :

When we arrived were all very tired. They came to us and told us that we would not all be able to stay together. I was the youngest so I would stay with eldest sister, but my other sister and two brothers had to stay on their own. Soon a couple came and took us. I never saw where my brothers and sister went.

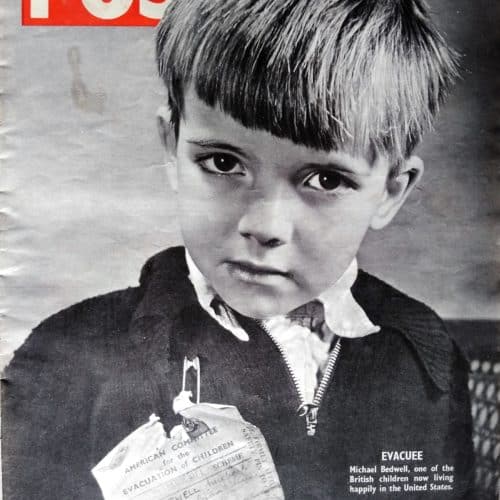

Some children were sent even further away than the British countryside. Some children travelled on ships to Australia, Canada and the United States of America. Many of the children sent abroad didn’t return to Britain until after the war was over.

Image copyright: Canterbury City Museums

Fascinating Fact

When children were evacuated they were given labels to fill in and fix to their clothing. This was so that the organisers knew who each child was and where they had been sent.

You can see the label in the photo of the little boy on the magazine cover.

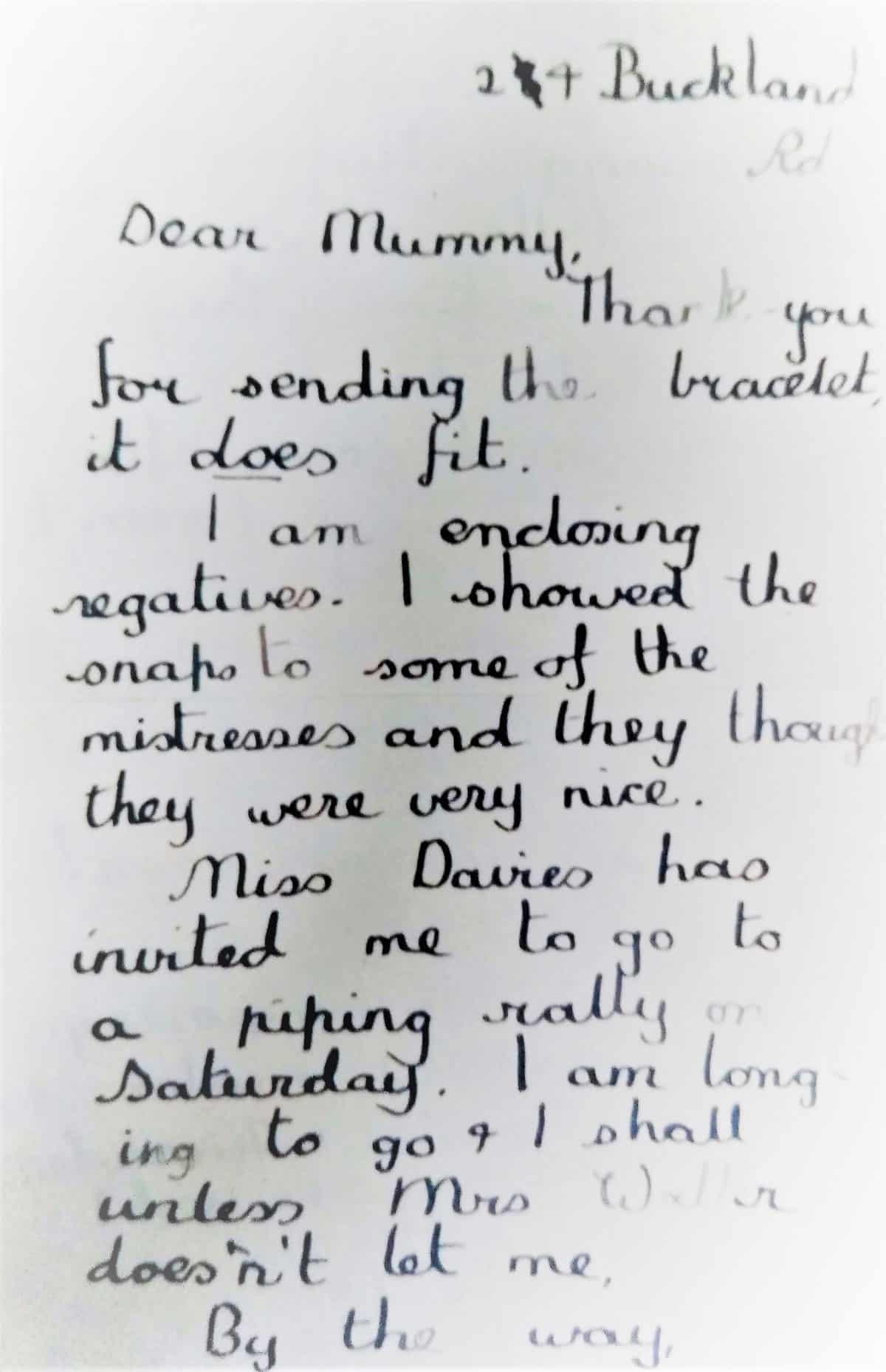

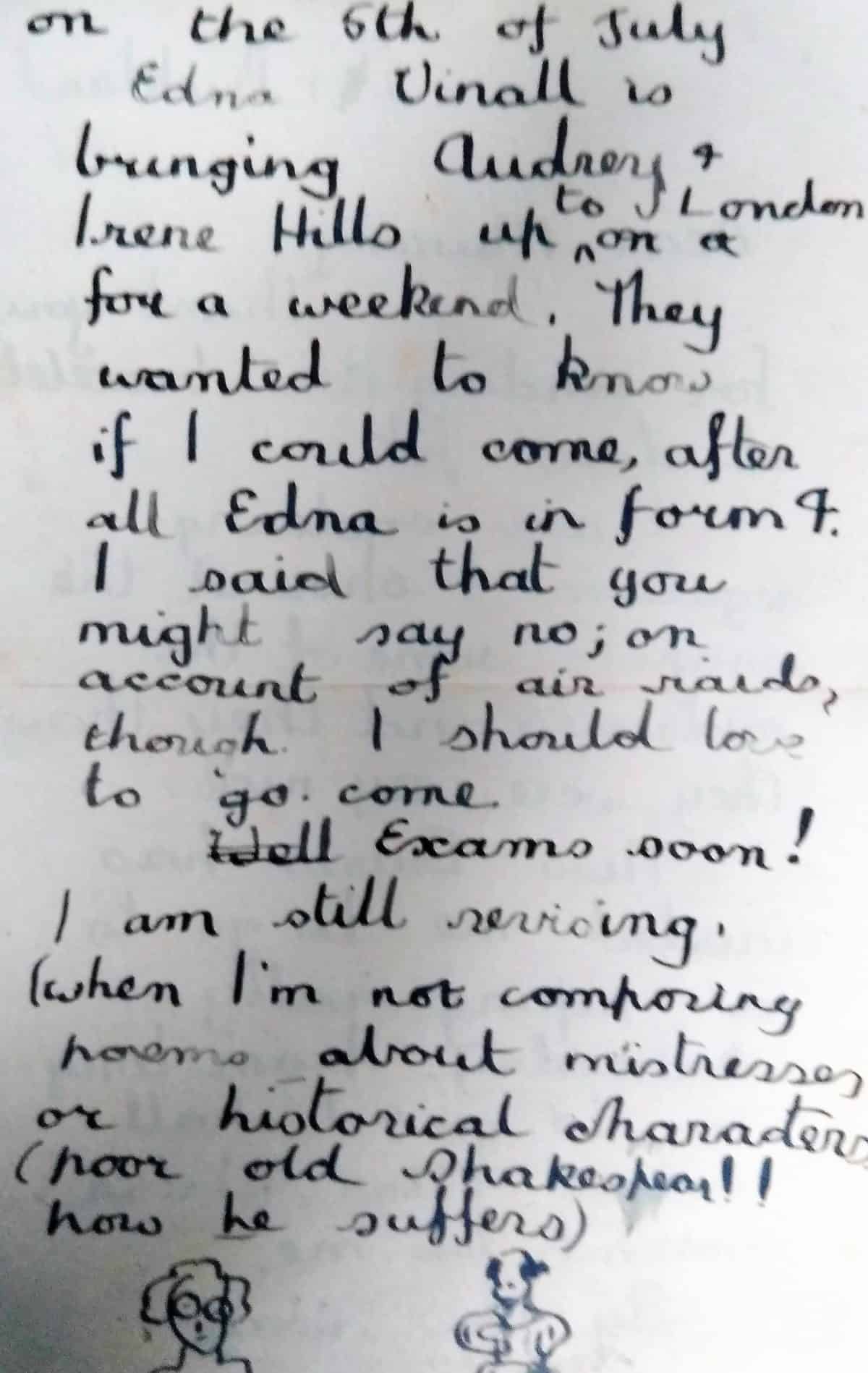

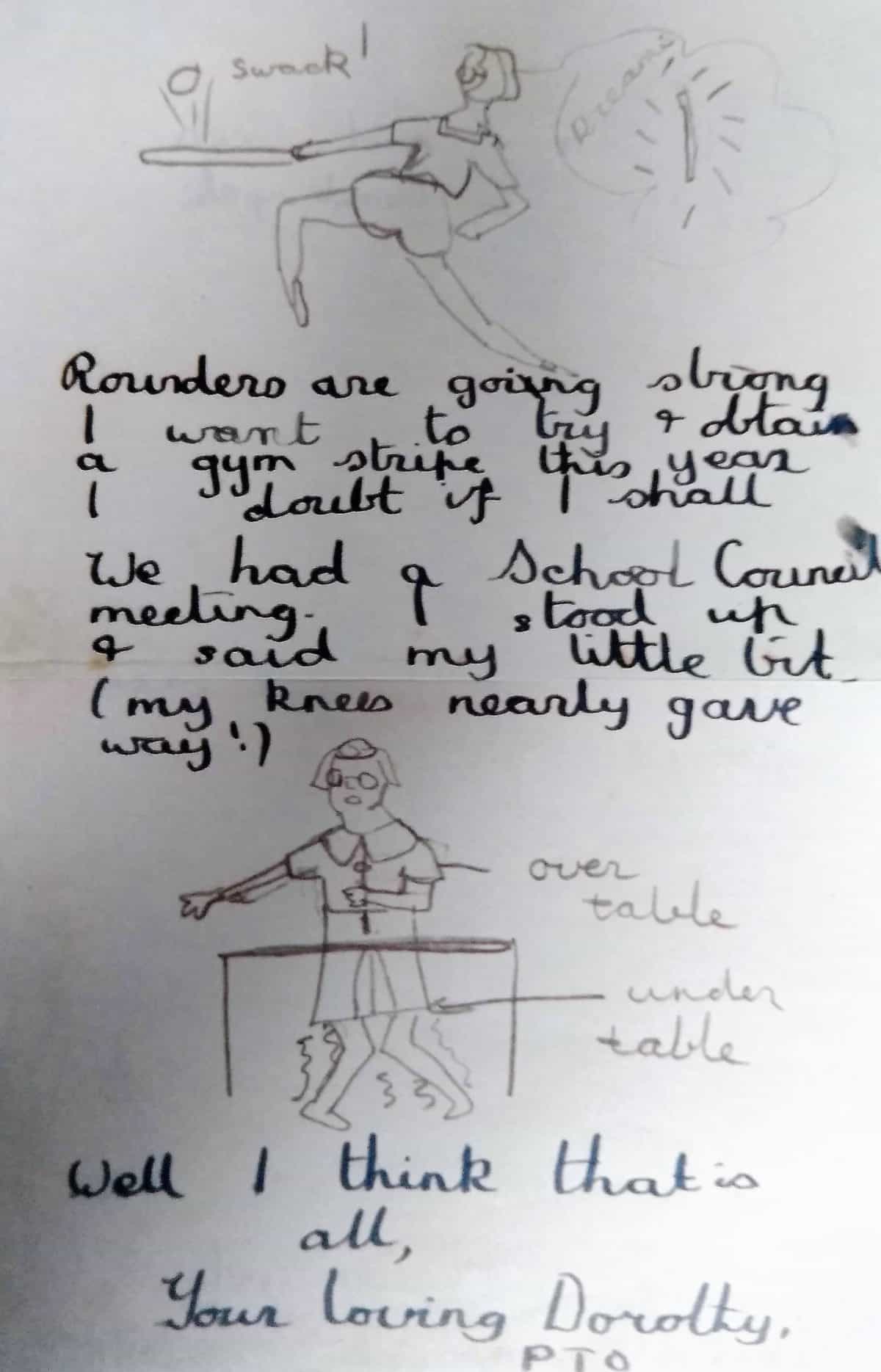

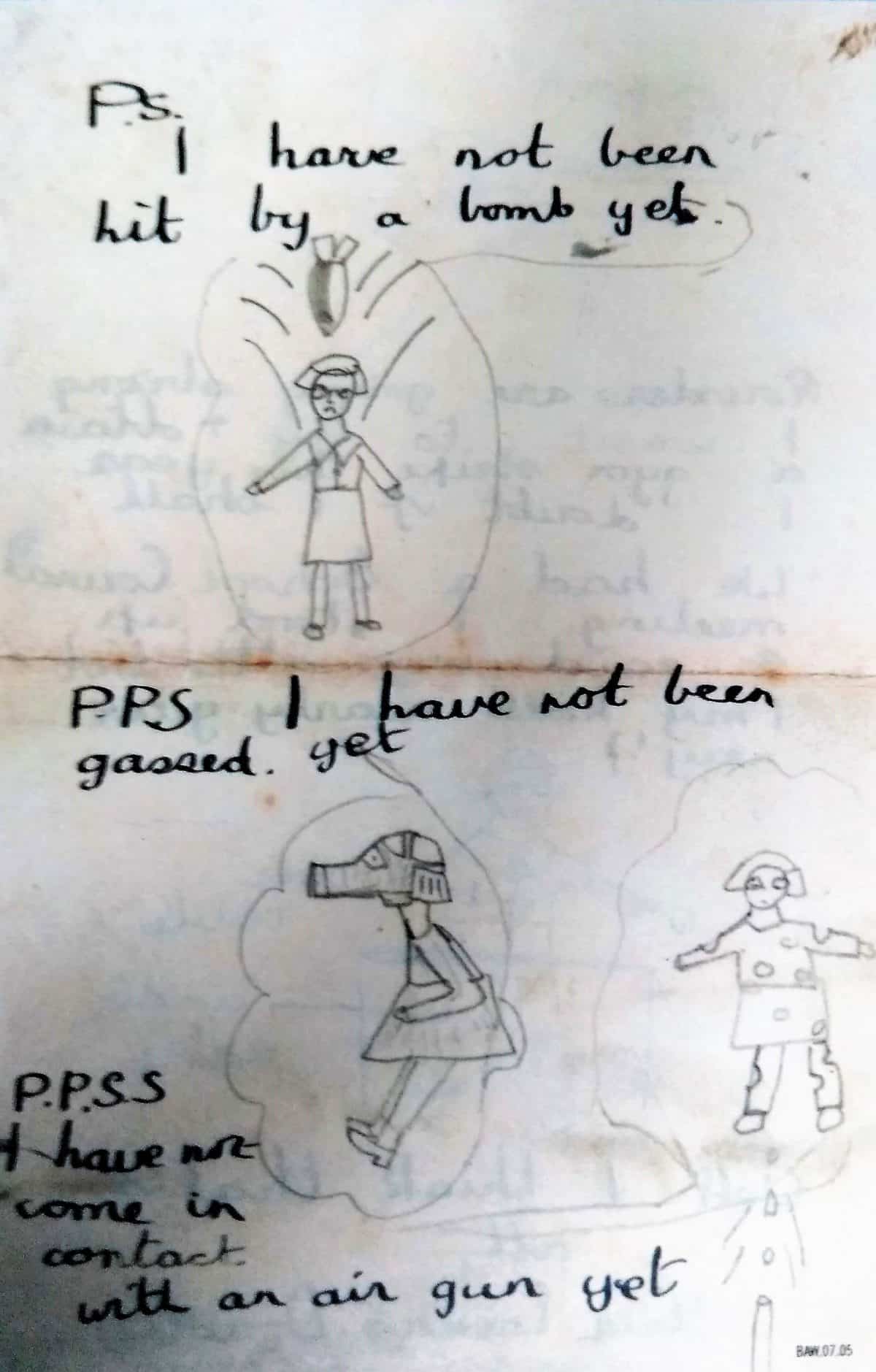

This is a letter written by an evacuee called Dorothy to her Mum telling her all about the school she was attending. Her letter contains lots of details about her school and she seems to have enjoyed being evacuated.

Some children had a wonderful experience of being evacuated, developing close bones with their foster parents and keeping in touch with them after they returned home. But others endured a miserable time. A Folkestone evacuee remembers the difficult start he had as an evacuee:

After a couple of weeks things were not right. They were cruel to us. We were told not to come home until late. Sometimes we had to go to school without breakfast. I cried quite a lot and told my teacher I wanted to go home. The next day we were moved to another house. They were very nice to us and made us welcome. We had good food and comfortable beds. They wrote to our parents to tell them we were OK.

For many city children the countryside was a shock. Some found it boring. The majority had never seen a farm animal before they were evacuated and, in some cases, older children were expected to work doing agricultural labour.

Here a Folkestone evacuee, aged 13 at the time, remembers being evacuated to a farm:

Never have been on a farm before it was quite an experience. It was rather late at night by the time we got to bed and I remember next morning getting up and eagerly looking out of the window to see what a farm was like. It was nothing spectacular at all, just a farmyard with all sorts of mess which was rather unusual for a townie.

Evacuation was a culture shock to the rural families too. The poverty of some of the inner city children who arrived in the countryside was a surprise and many thought that these children had been neglected at home.

Fascinating Fact

Of the children who were evacuated in 1939 almost half of them had returned home by early 1940. This was because of the period called the ‘Phoney War’ were there was no bombing. This included some children from Folkestone who were sadly killed in the bombing raids on the town. In total 7,736 children were killed during the Blitz and another 7,622 were seriously injured.