Print of the Roman amphitheatre at Nimes in France, collected by Thomas Man Bridge while on his Continental Grand Tour in the 1830s. This forms part of the Master Collection at Folkestone Museum.

Object: Master

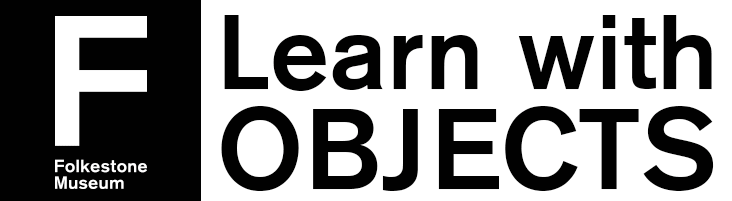

Watercolour – Temple of Venus, Pompeii

Watercolour collected by Thomas Man Bridge. Number 46 shows tourists exploring the Temple of Venus, Pompeii. Excavated 1861. Brightly coloured wall paintings can be seen in the background.

Gouache painting – Road up Vesuvius

Gouache painting. Road up Vesuvius. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

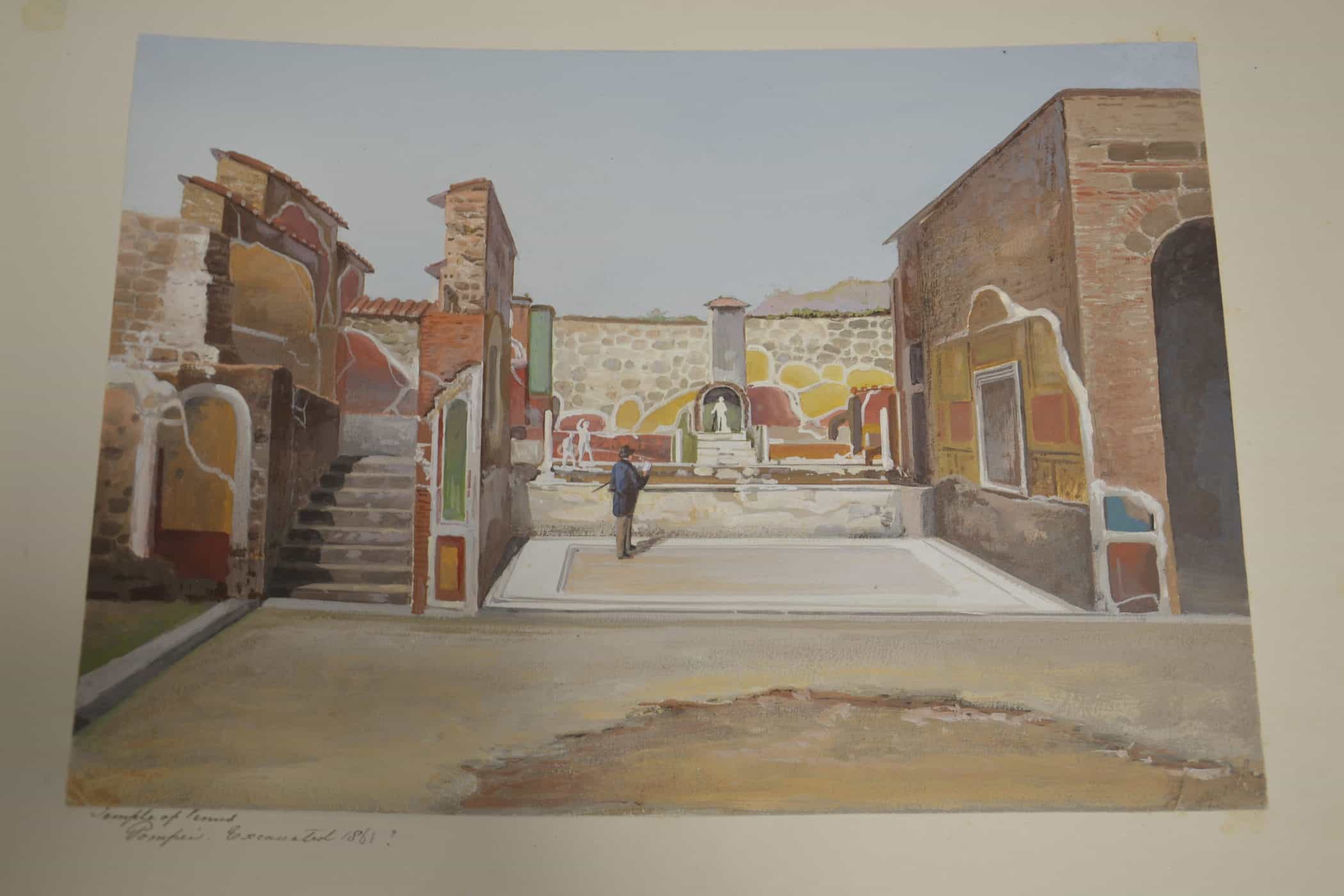

Gouache painting – Funiculare railway

Gouache painting Funicolare railway – by night. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Gouache painting – The Crater 1883

Gouache painting The Crater 1883. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

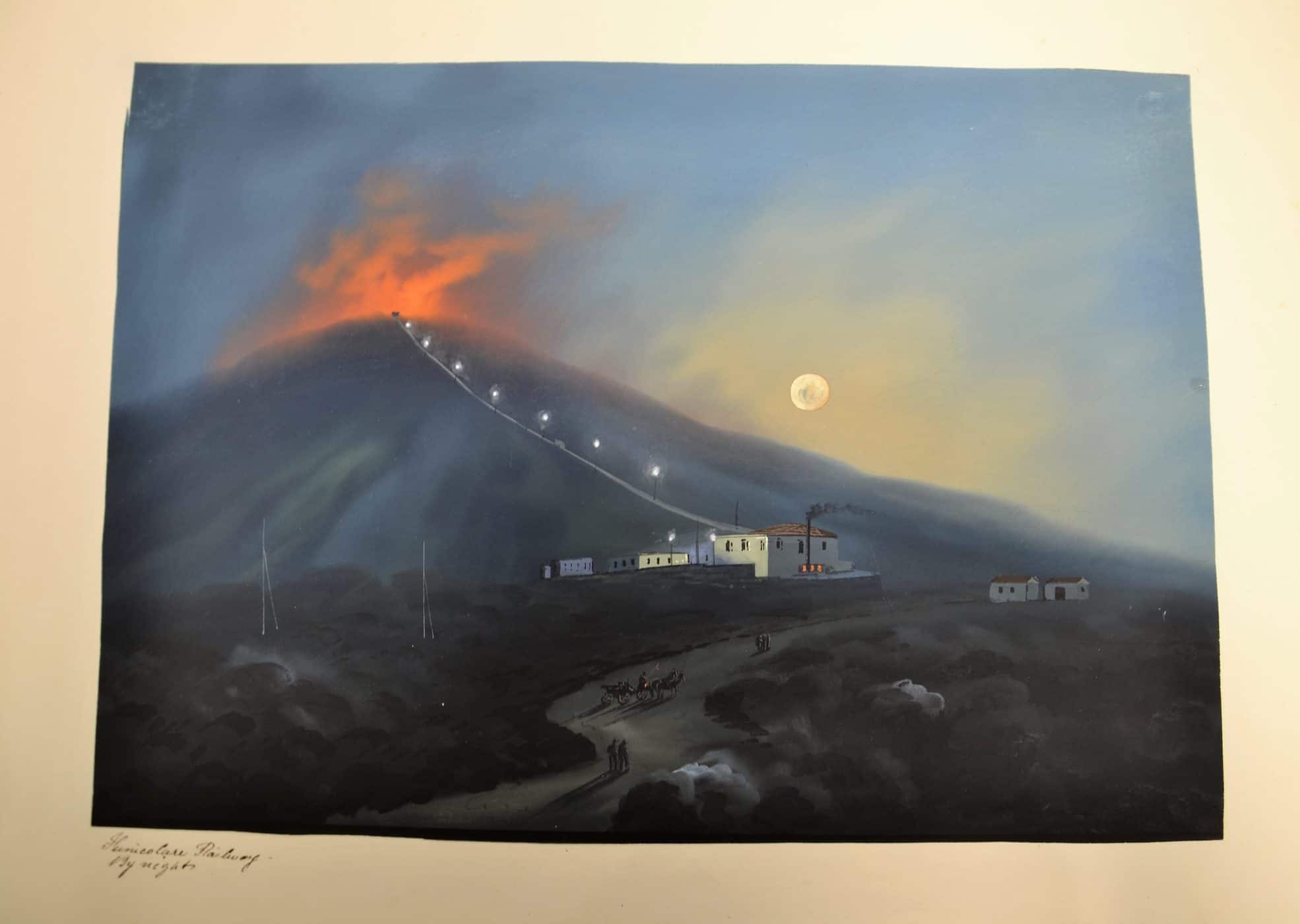

Gouache painting – Aquasus volcano

Gouache painting Aquasus [poss] Volcano – which started up five miles from Sicily. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Gouache painting – Earthquake at Ischia

Gouache painting The Earthquake at Ischia. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

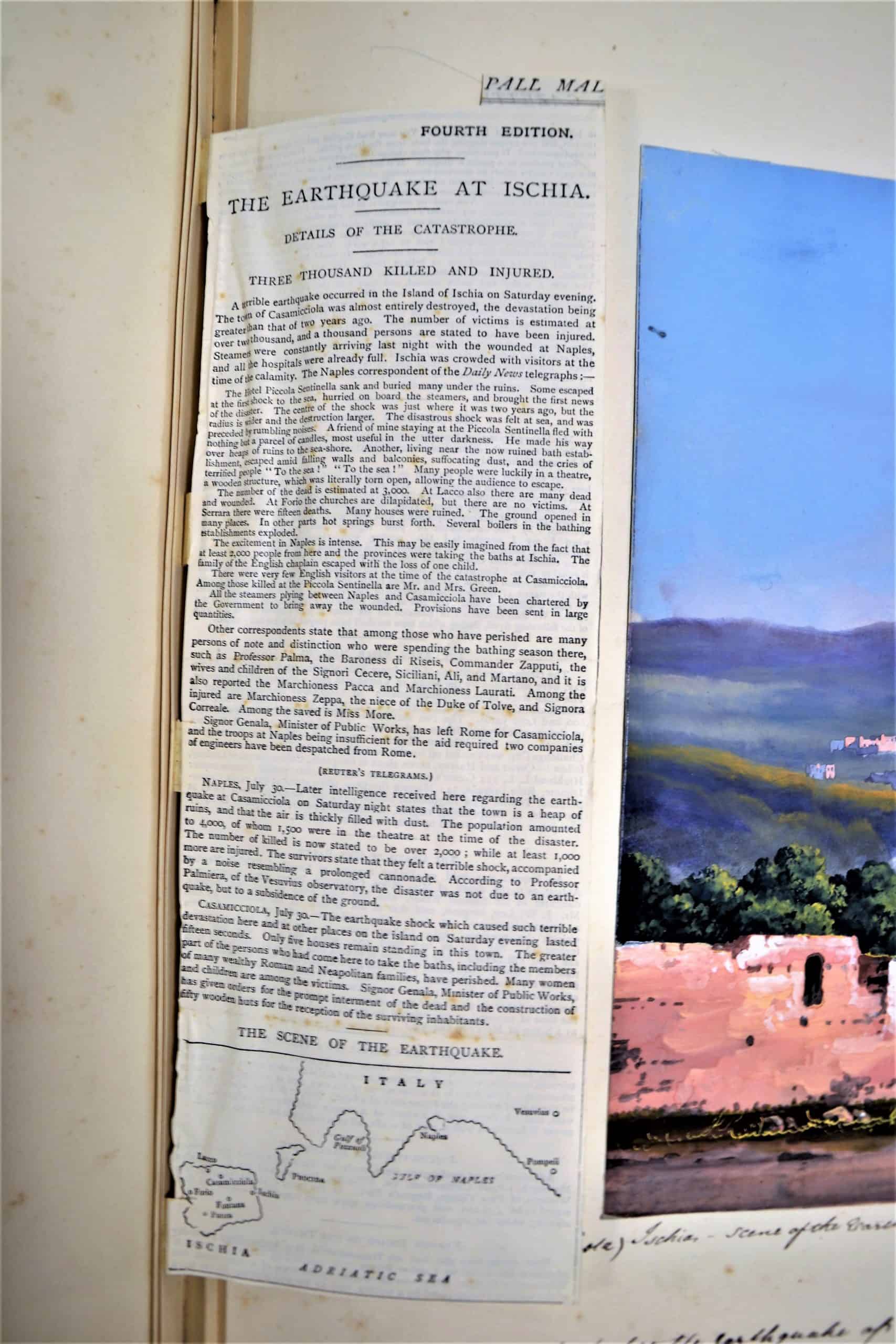

Newspaper cutting – Earthquake at Ischia

The Earthquake at Ischia. Newspaper clipping. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Drawing – French postilion and his boots

Drawing of a French postilion and his boots. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Print of a bullfight

Print of bullfight. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Gouache painting -Vesuvius eruption

Gouache painting of Mount Vesuvius eruption. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Gouache painting – On the road to Posilipo

On the Road to Posilipo. Naples with Vesuvius in 1868. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

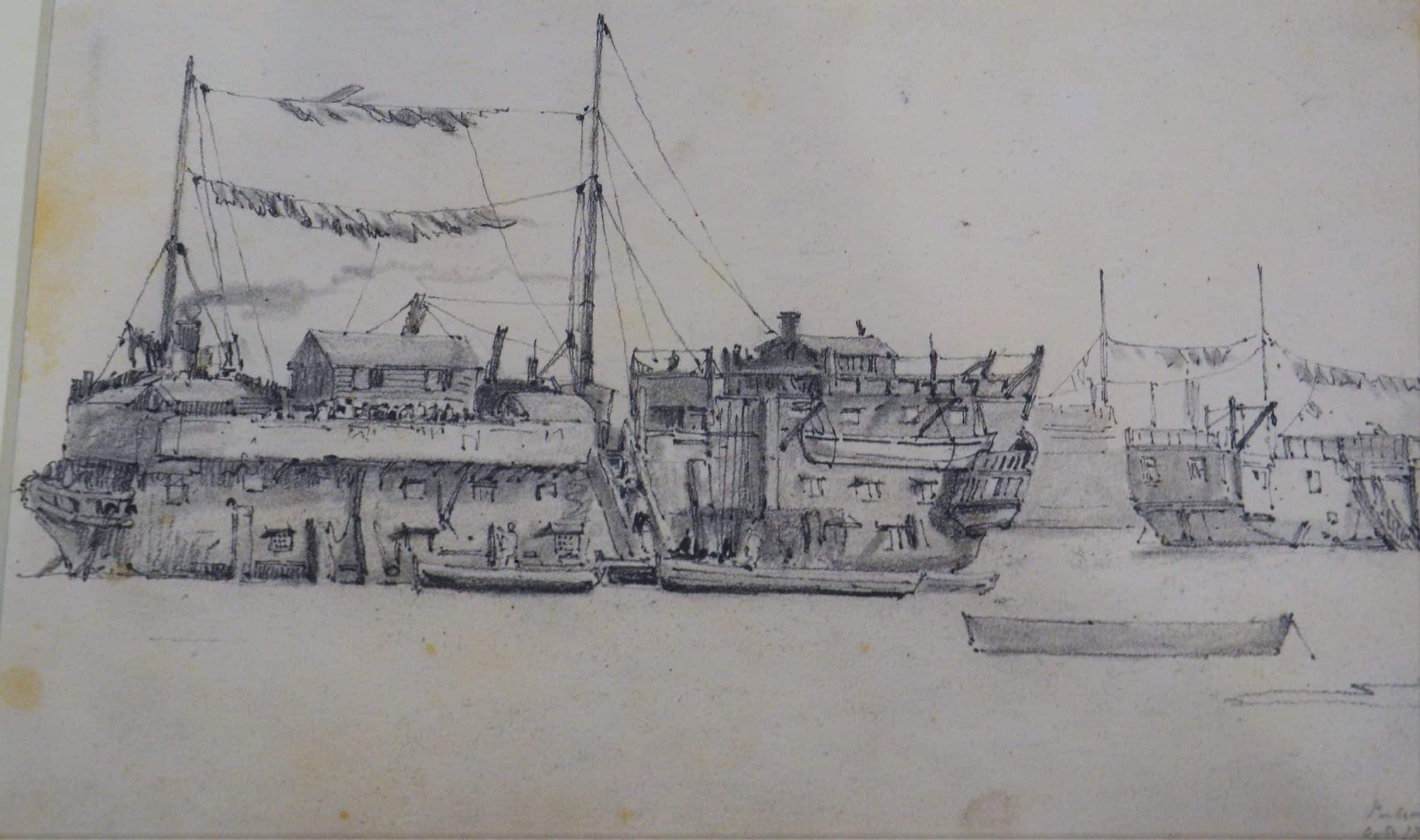

Drawing of a beached hulk on the Thames

A beached hulk on the Thames. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

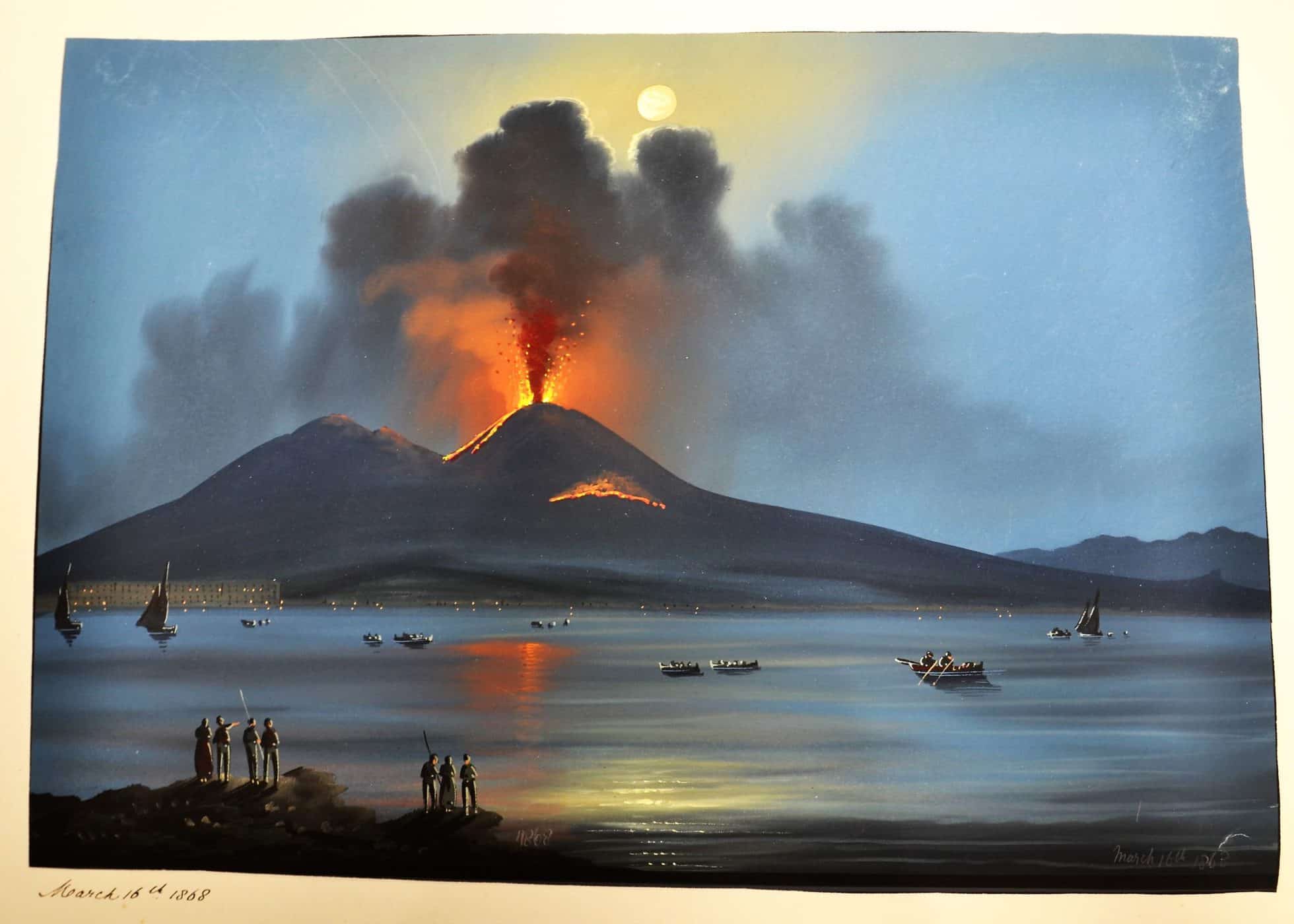

Gouache painting – Vesuvius eruption 1868

Gouache painting of Vesuvius eruption 23 March 16th 1868. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

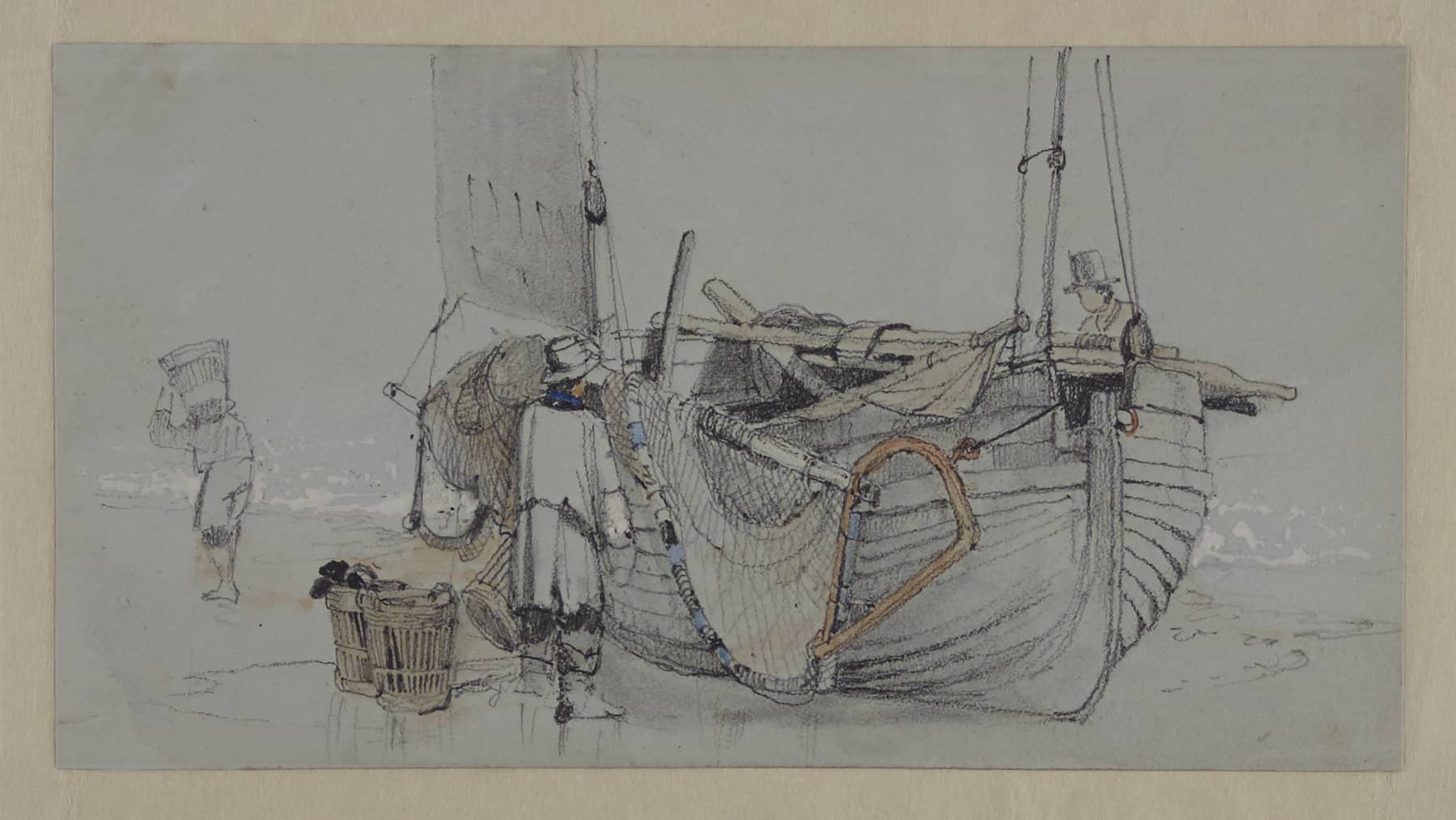

Drawing of fishermen unloading their catch

Fishermen unloading their catch. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

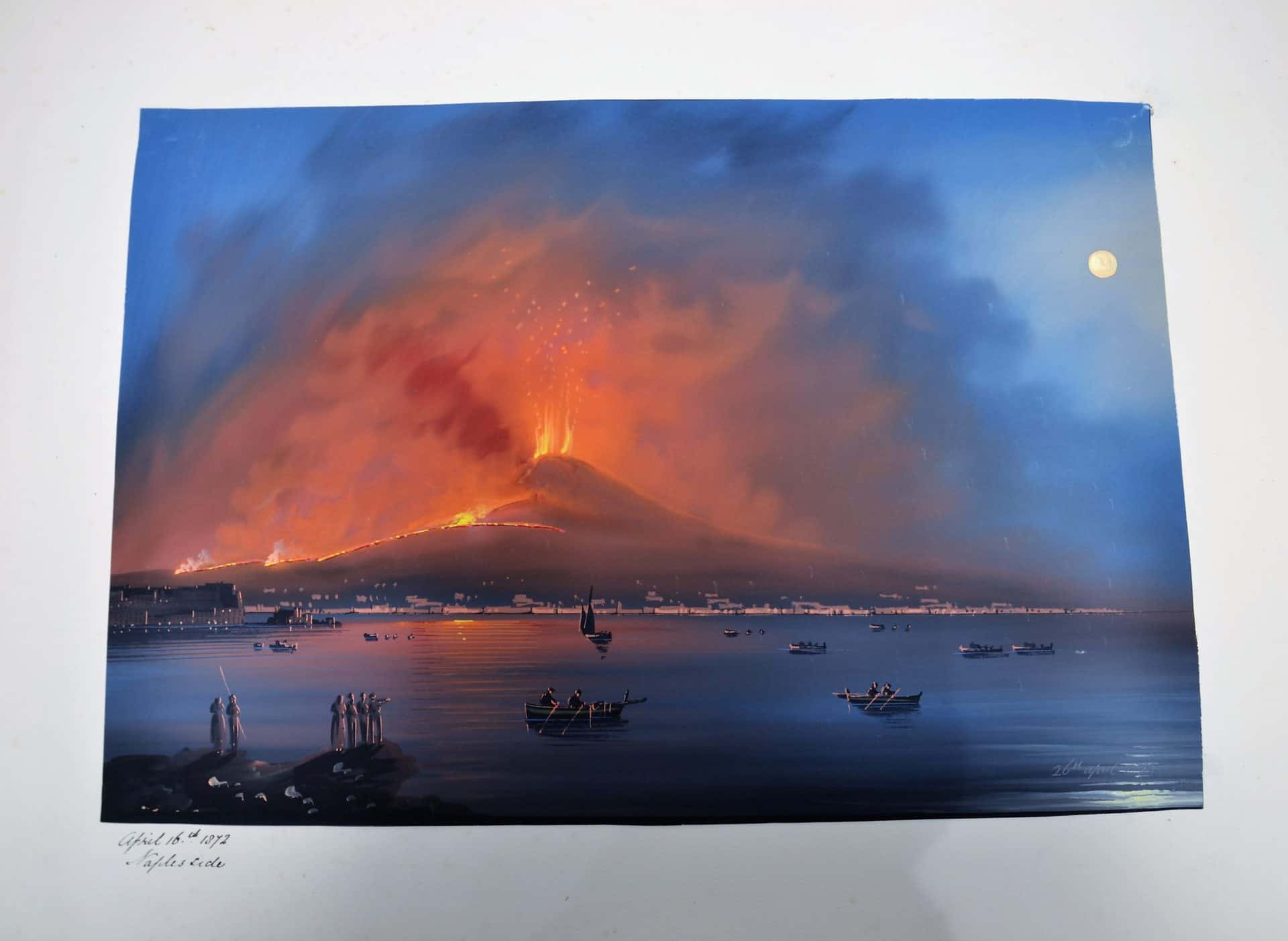

Gouache painting – Vesuvius eruption 1872

Gouache painting of Vesuvius eruption 24 April 16th 1872 Naples side. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Drawing of Boulogne fisherwomen

Pencil drawing of Boulogne fisherwomen. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Watercolour of The Harbour, Naples

Watercolour of The Harbour, Naples. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

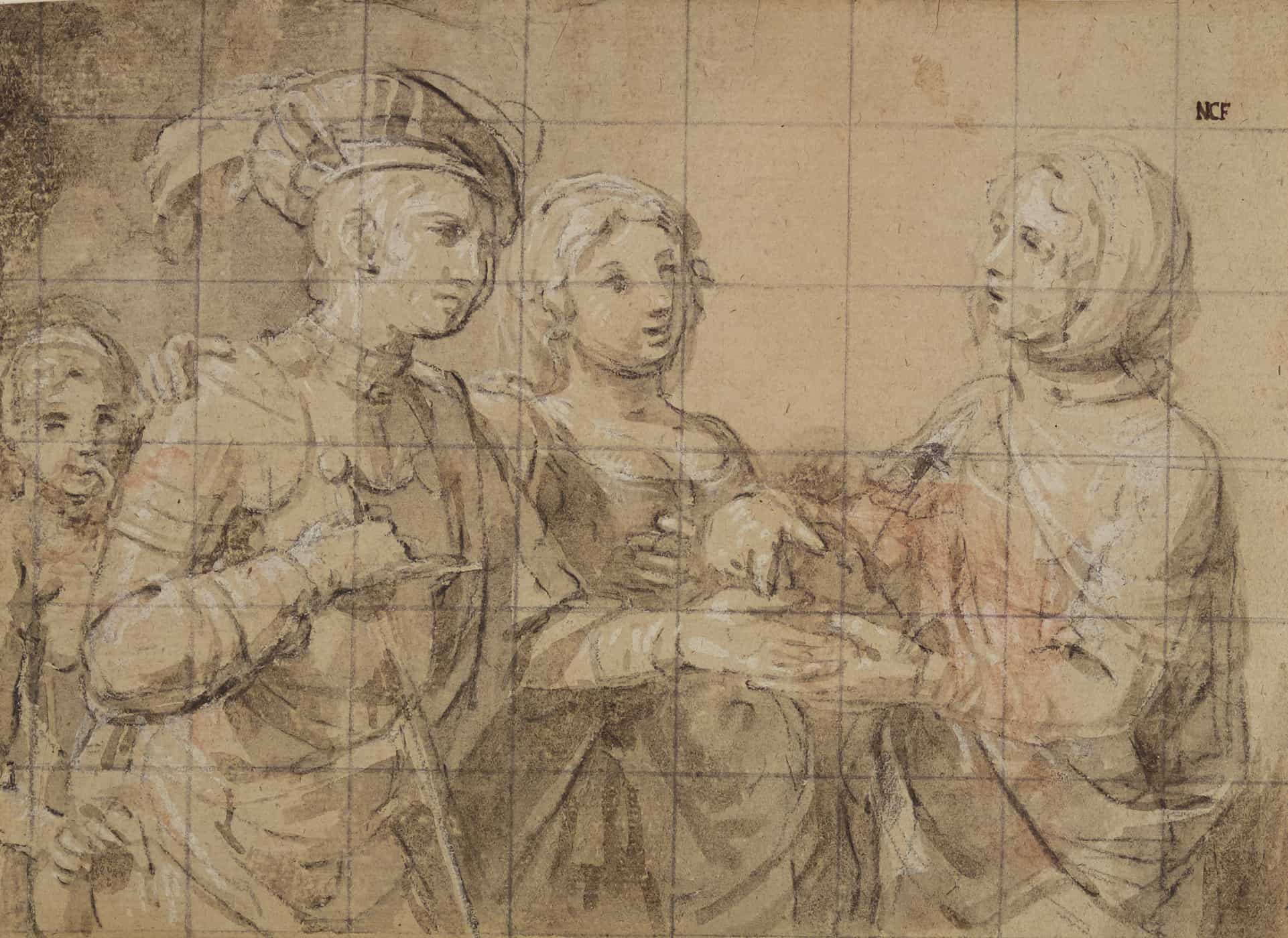

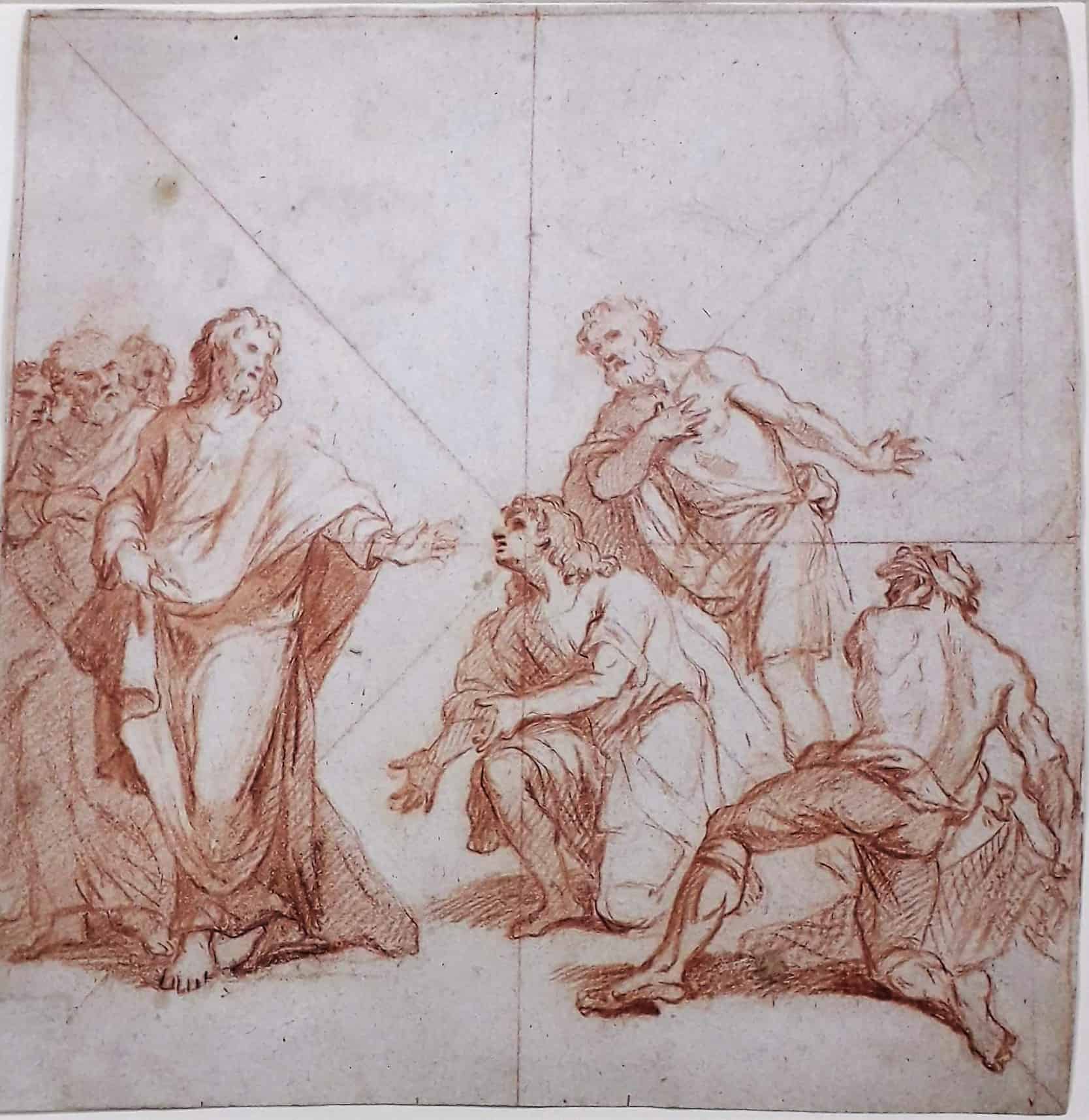

Drawing – The Fortune Teller

The Fortune Teller.Black and red chalk, brown wash heightened with white.

Print – Panorama of Rome

Panorama of Rome. Panoramma di Roma, Antica e Moderna.Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

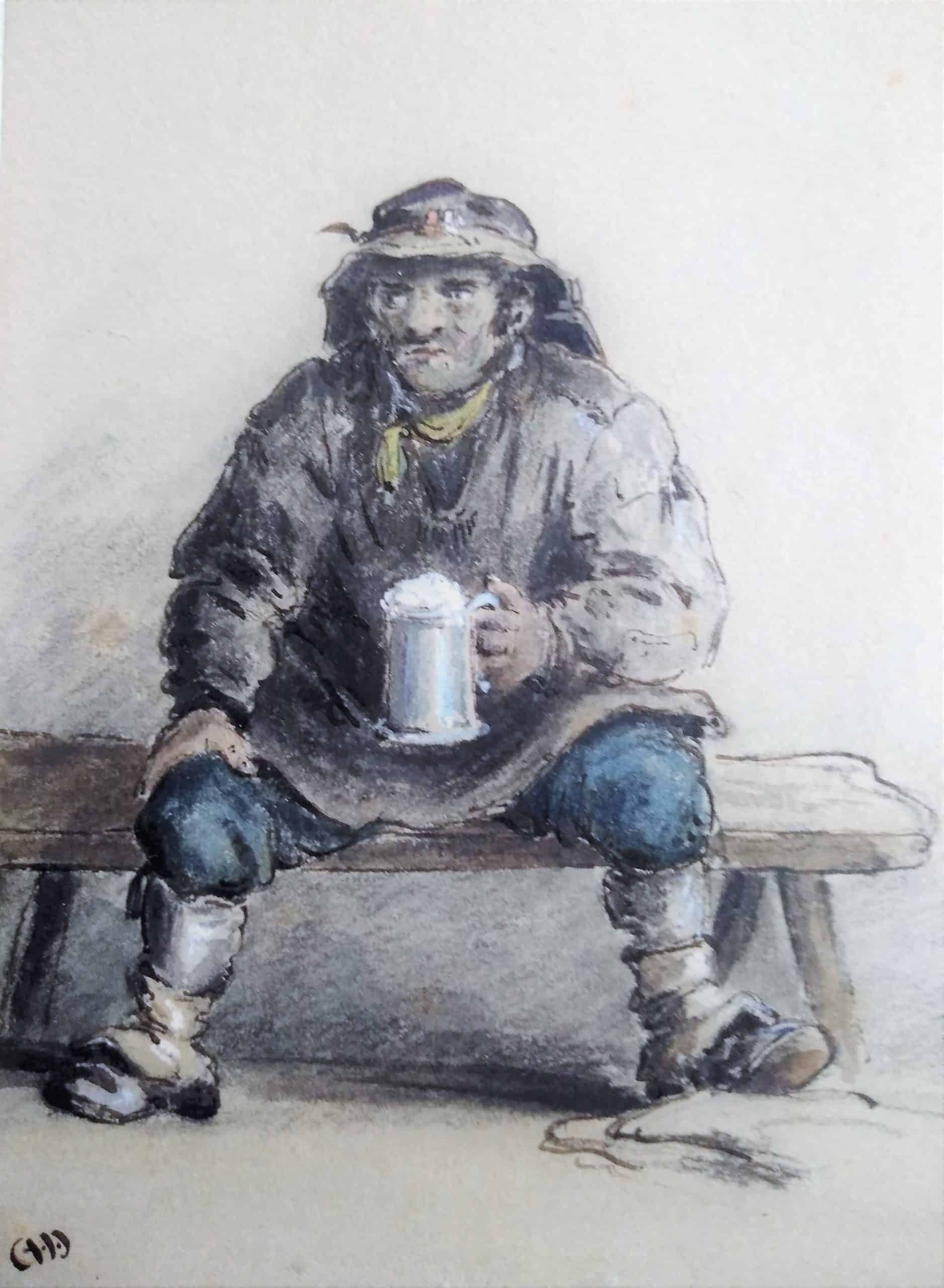

Print – Coal porter drinking beer

Portrait of a coal porter drinking beer. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

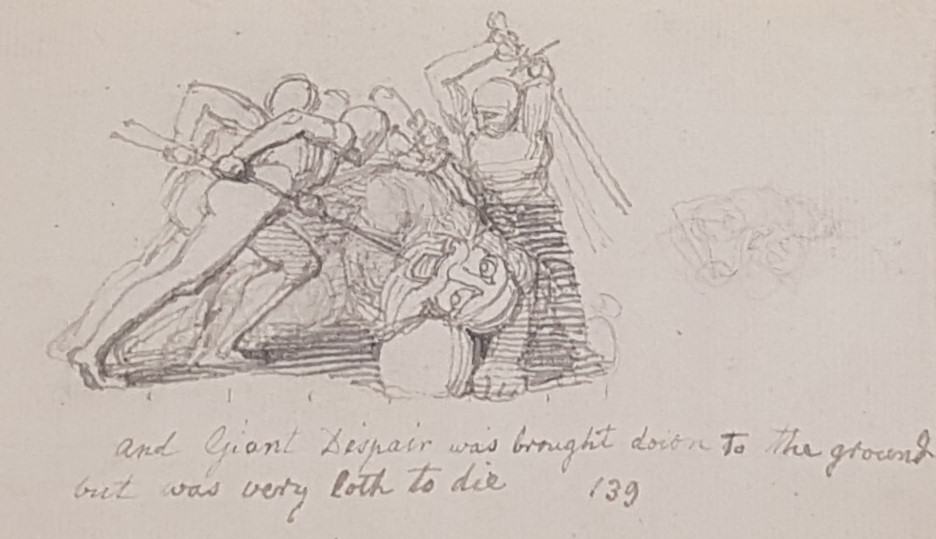

Drawing – Illustrations for The Pilgrims Progress

Thomas Stothard – the artist as illustrator. Illustrations for The Pilgrim’s Progress. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Drawing – Illustrations for Tristram Shandy

Thomas Stothard – the artist as illustrator. Illustrations for Tristram Shandy. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Drawing – Study of a Youth

Study of a Youth, his left arm outstretched. Black and red chalk, pen and brown ink drawing. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge.

Print – Glacier in the Alps

Print of glacier in the Alps. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

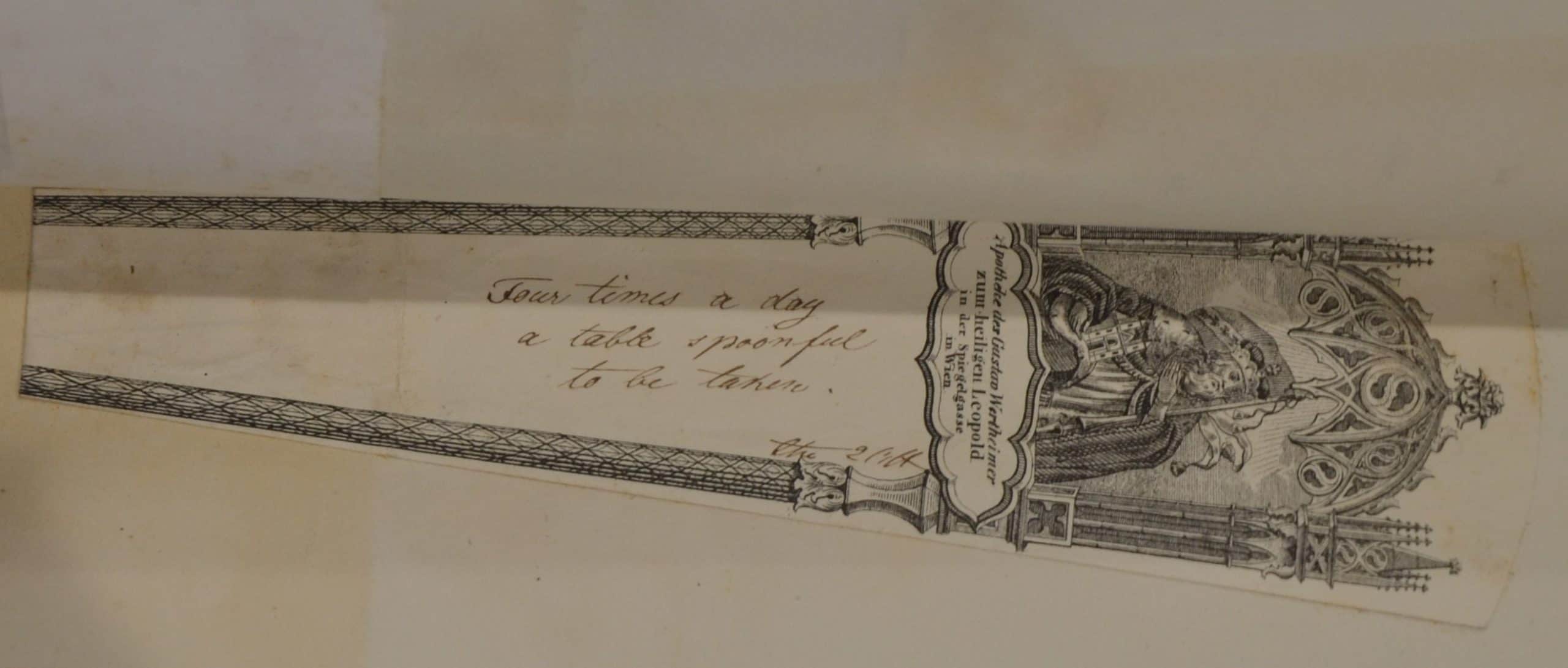

Pill or medicine packet from Vienna

Pill/medicinal powder tube from Vienna. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Pill or medicine packet from Vienna

Pill/medicinal powder tube from Vienna. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print – The Leaning Tower of Pisa

Print of the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print – Bird’s eye view of Venice

Print, bird’s eye view of Venice. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print of Venice

Print of Venice. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print – The Doge’s Palace from the sea, Venice

Print of The Doge’s Palace seen from the Sea Kent Master Collection Catalogue no 33B. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print of a gondola, Venice

Print of a gondola. Kent Master Collection Catalogue no 33F. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

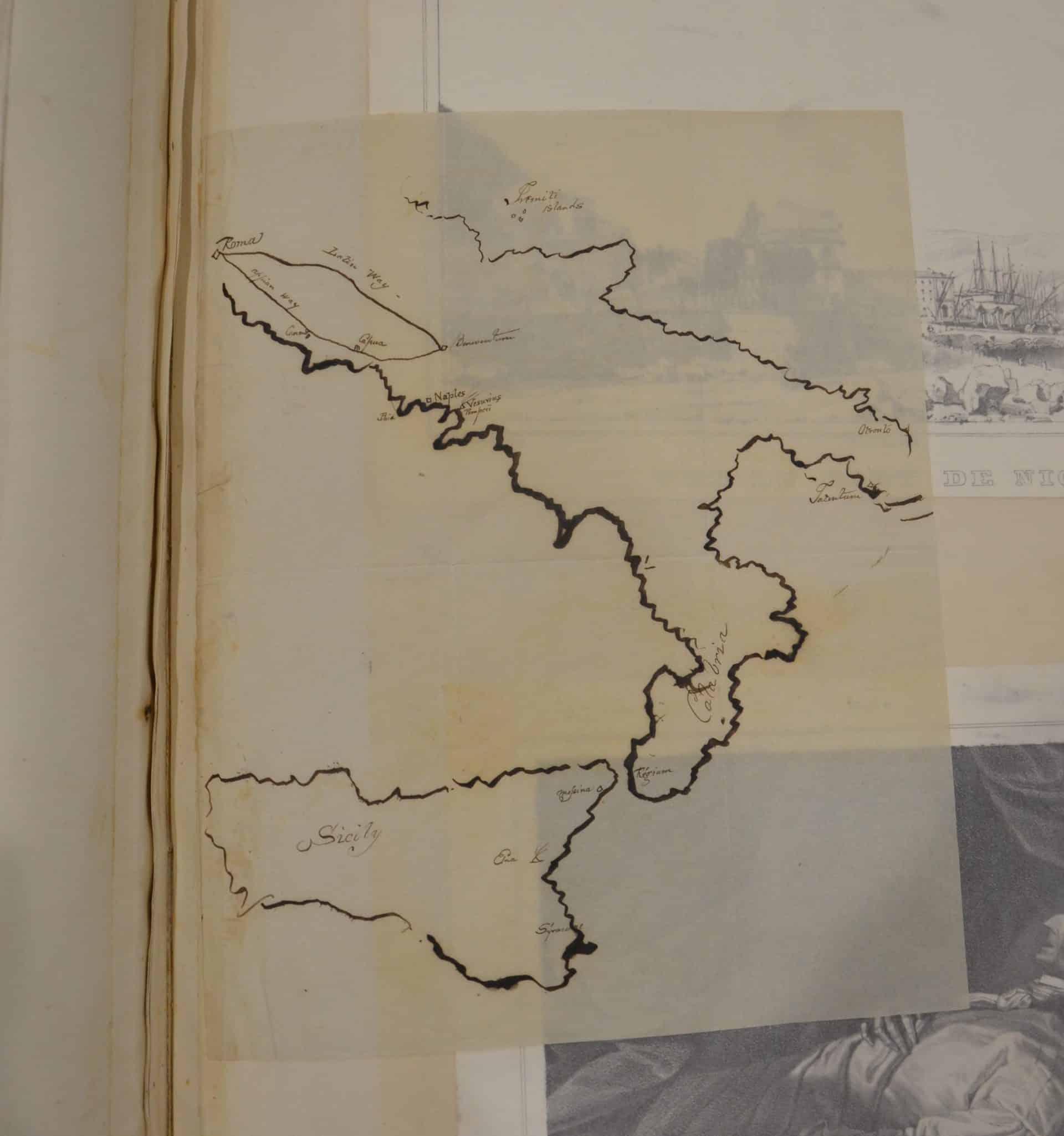

Map of Southern Italy and Sicily

Handwritten map of Southern Italy and Sicily. Drawn for/by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print of pizza seller

Print of pizza seller. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print of Naples and Vesuvius

Print of Naples and Vesuvius. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Gouache painting – Naples from the Sea

Naples from the Sea. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Gouache painting – Several new craters formed

Several new craters formed. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print – Valetta, Malta

Valetta. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

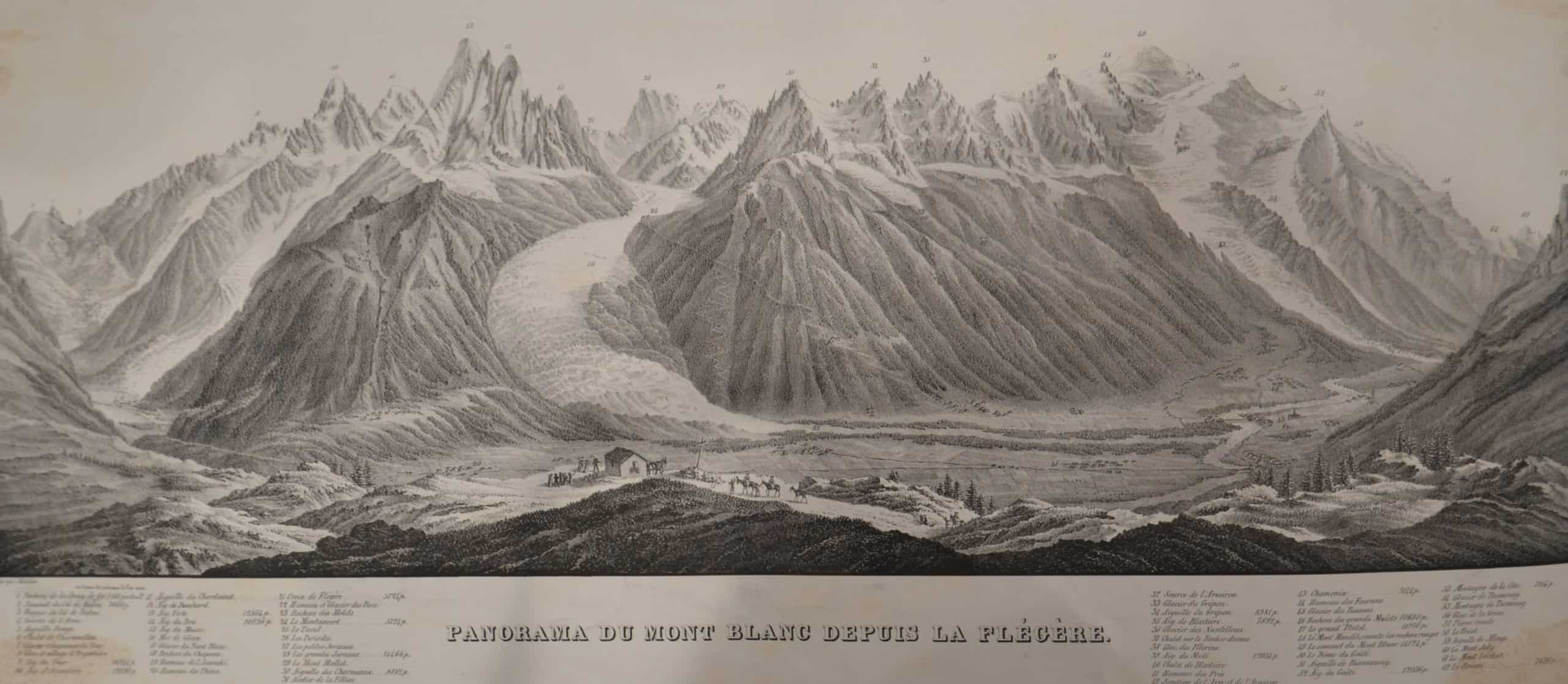

Print – Mont Blanc massif

Print of Mont Blanc massif collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

Print – Valetta, Malta

Valetta. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

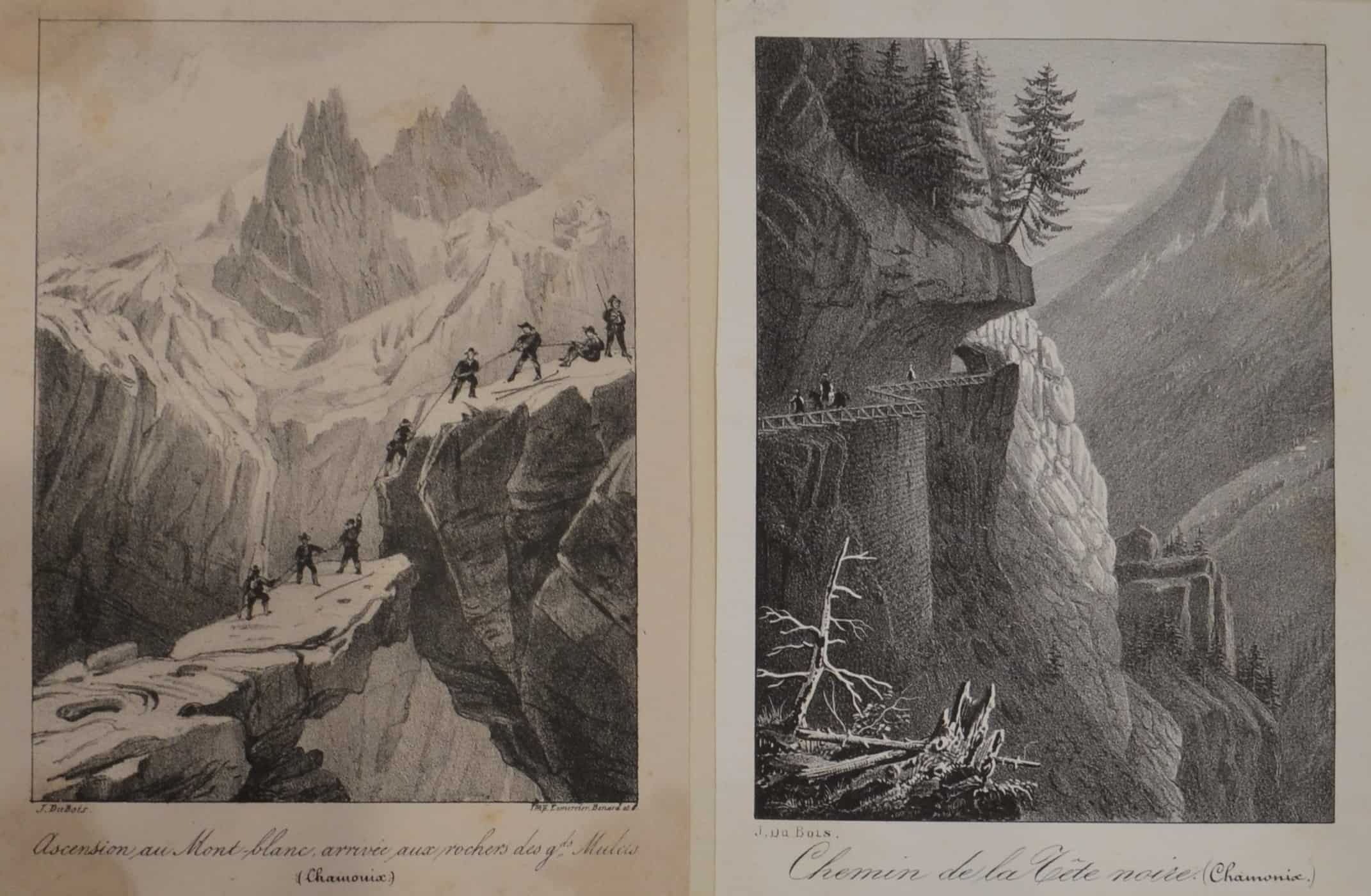

Print – Ascension au Mont Blanc

Print of Ascension au Mont Blanc. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

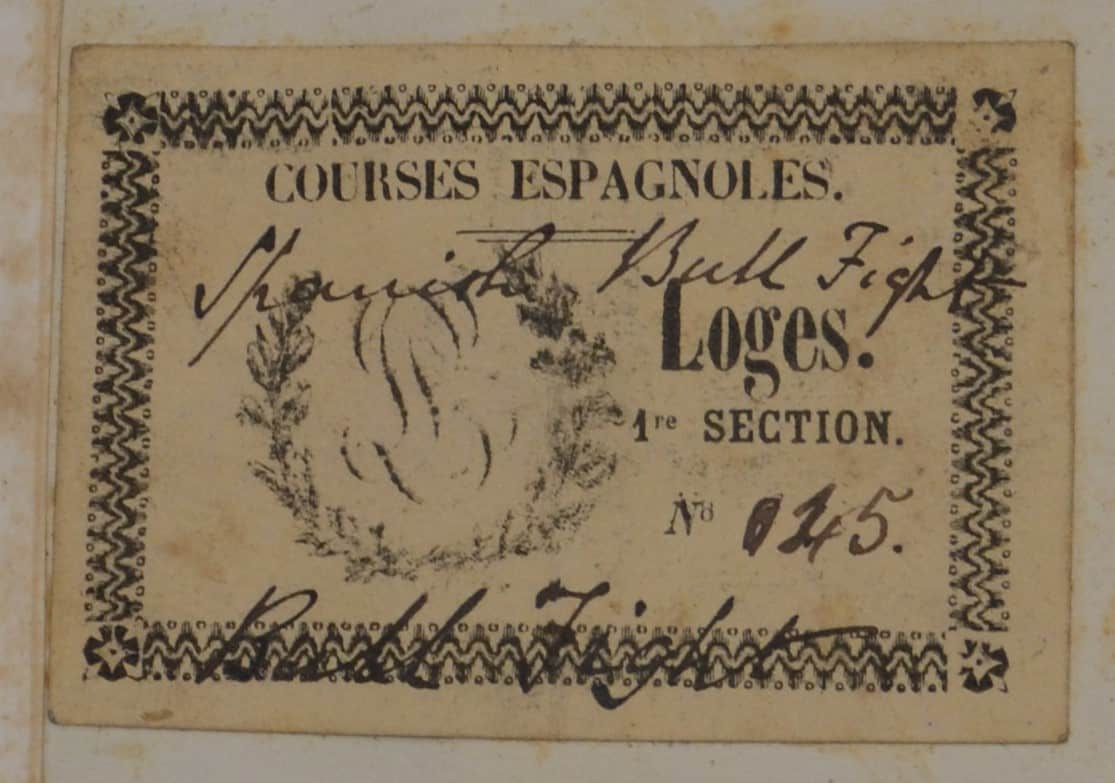

Ticket to a bullfight

Bullfight ticket. Collected by Thomas Man Bridge on his Continental travels (1837-1841).

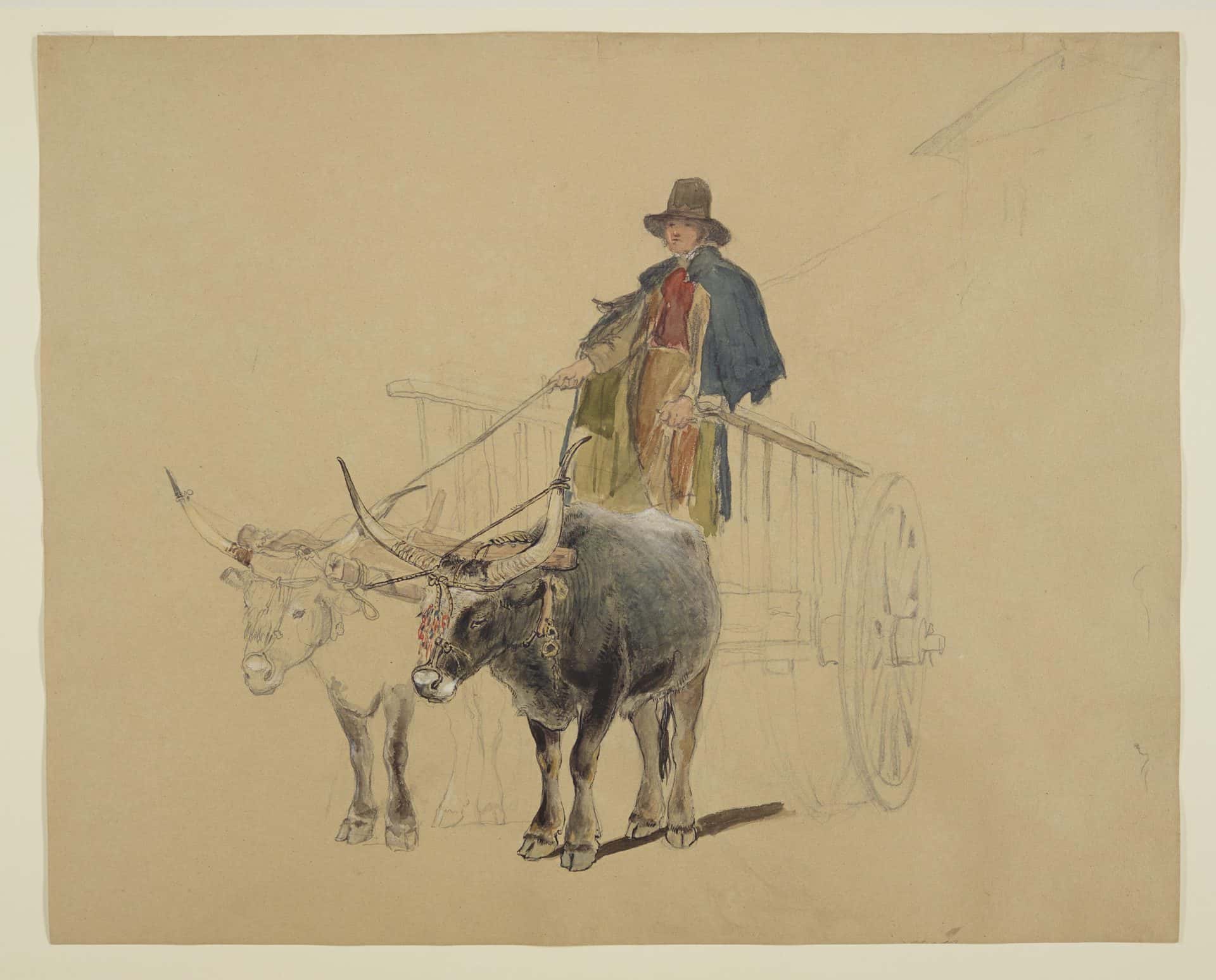

Drawing of a Roman ox cart

A Roman Oxcart by William Collins RA (1788-1847). Pencil, pen, black ink and watercolour heightened with white, on light brown paper, 364 x 455mm. Purchased by Thomas Man Bridge at Christies auction in 1847.

Drawing of the Trajanic frieze on the Arch of Constantine, Rome

Copy of Trajanic frieze on the Arch of Constantine, Rome. This drawing depicts a battle, with cavalrymen and foot soldiers.The men in armour are Roman soldiers. They are wearing plumed helmets and body armour or ‘cuirasses’. The man on the left with a flying cloak but no helmet is thought to represent the emperor Trajan.The men without armour are Dacians – ‘barbarians’ from the area of central Europe now in Romania.The battle scene is a Roman sculpture from the time of Trajan. It is a relief sculpture from the Great Trajanic Frieze that was once in the Basilica Ulpia in Trajan’s Forum, Rome. During the time of the emperor Constantine, before the fall of the Roman Empire, this sculptural relief was removed from its original location and incorporated in a new Arch of Constantine. This arch reused many Roman sculptures from the time of earlier emperors.

Drawing of Roman reliefs on the Arch of Constantine

Copy of Roman reliefs on the Arch of Constantine, Rome. On the left of the drawing is a depiction of a Roman boar hunt. Toga-clad Romans on horseback – the emperor Hadrian and his men – are attacking a wild boar. Can you see its rough skin, hooves and tusks? On the right of the drawing is depicted a Roman sacrifice to a deity. Two men in togas, representing the emperor Hadrian and a companion, stand on the left of an altar. A sacrifice is burning in front of a sculpture of the Roman god Apollo, recognisable by the lyre he holds. To the right of the altar a toga-clad man is holding a horse for Hadrian. On the bottom of the drawing is a pencil sketch of Roman figures, some of them standing and others seated. They are part of a relief sculpture from the time of Constantine. The two larger scenes are copies of Roman sculptural reliefs in the form of medallions from the time of the emperor Hadrian. The sketch along the bottom is from a long narrow frieze made in the time of Constantine. The frieze was installed below the two medallions on the Arch of Constantine in Rome. This arch reused many sculptures from the time of earlier emperors. It showed that Constantine was paying tribute to his predecessors but also made him their equal.

Drawing of detail from the Expulsion of Heliodurus

Unknown artist after Raphael. Detail from the Expulsion of Heliodurus Black chalk and brown wash on paper, 265 x 425 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.122. In this drawing a Roman-style cavalryman is attacking a man in armour lying on the floor. The horseman looks angry. Coins have spilled out of fallen pot. This drawing is a copy of the Expulsion of Heliodorus in a wall painting by the Renaissance artist Raphael at the Vatican in Rome.

Drawing of St George and the dragon

Unknown artist Saint George and the Dragon Black chalk, pen and grey ink, grey wash on paper, 219 x 320 mm The inscription top left on the drawing refers to the artist Luca Cambiaso (1527-1588). Someone in the past has attributed this drawing to Cambiaso, a painter from Genoa who went to work for the court of King Philip II of Spain. The art historian Mary Newcome Schleier suggested it was more like the work of Nicolosio Granello (about 1500-1560), another artist from Genoa.

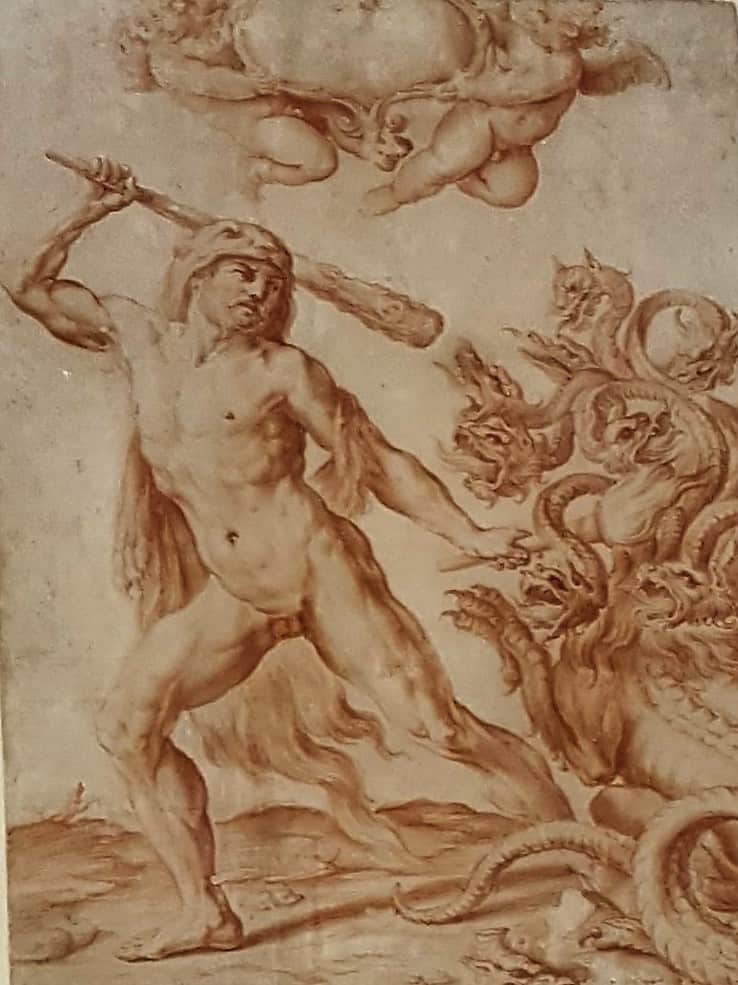

Drawing of Hercules slaying the Hydra

Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610-1670) Hercules Slaying the Hydra. Brown wash on paper, 205 x 146 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.57 The man with a club is mythical Greek hero Hercules. He is wearing a lion skin. The monster has seven heads. It is a Hydra, or watersnake. Hercules personified physical strength and courage. His battle with the Hydra was the second of hisTwelve Labours,

Drawing – Studies of a swan

Alexandre-François Desportes (1661-1743) Studies of a Swan. Black, red and white chalk on light-brown paper, 226 x 332 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.26 Desportes has written himself helpful notes about colour. Below the swan’s foot he has written in French ‘les pates noire grisatre’, meaning ‘the feet greyish black’. On the top left he has written about the colour of the swan’s head and neck. Colour notes like these helped his assistants recreate images of animals with vivid realism.

Drawing – Studies of deer with a city beyond

Attributed to Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) Studies of Deer with a City beyond.Black lead, pen and brown ink on paper, 157 x 202 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.7. The artist has observed and sketched lots of different behaviours of deer. One has a mouthful of grass; several others are nibbling grass; one is licking its foot. Most are standing and three are lying down. By sketching this variety of positions, the artist had a wide range to choose from when he later came to make a painting in his studio. In the background of the drawing is a city.

Engraving – The Holy Family with a dragonfly

Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) Holy Family with a Dragonfly .Engraving, 235 x 183 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.174. The dragonfly is on the bottom right. But it might be a butterfly: butterflies symbolise the Resurrection of Christ, a caterpillar ‘resurrecting’ into a beautiful winged butterfly. In the middle of the picture is the Holy Family: Mary, baby Jesus and Saint Joseph. Joseph appears tired and is fast asleep. Mary is looking tenderly at Jesus. Durer and other German artists of his time pictured Mary, Jesus and Joseph behaving like ordinary people and showing emotions. In the distance is a harbour leading to open sea.

Engraving – Melancholia

Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) Melancholia Engraving, 235 x 183 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.175 The dog is lying curled up on the left. It is a greyhound, known for its speed. The tools lying at the front would be used by a carpenter. The one centre left is a plane. It contains a sharp blade and is pushed by the handle to remove thin strips of wood. The tool centre right is a saw, with jagged teeth. There are also tongs peeping from below the skirt-hem of Melancholy, a straight edge below the saw, and some iron nails. Can you find a hammer? These carpentry tools and nails allude to the crucifixion of Christ. On the wall to the left of the bell are an hourglass and a set of scales. The hourglass and bell represent Time. The scales are a reminder that Christians believed good and bad things done by someone during their life would be judged at their death, to decide if they went to Heaven or Hell. The winged cherub is sitting on a millstone beside a ladder. A millstone can make you sink, while a ladder can take you up high. The rainbow behind symbolises hope. Melancholy is holding dividers or compasses. Along with the sphere and polyhedron, these symbolise Geometry. Behind the polyhedron is a crucible, used by alchemists who tried to turn ordinary metal into gold. At her waist Melancholy has keys, signifying power. The purse at her feet is wealth. Durer’s print is about the difficulties of creativity. Melancholy is a form of depression and was linked to creative genius. This print is one of Durer’s master engravings – his best works, for which he was most famous. (The Folkestone print is one of many copies made by contemporaries of Durer.) Durer made both engravings and woodcuts, and was the most important early printmaker.

Drawing – A man drawing another asleep

Attributed to Agostino Carracci (1557-1602) A man drawing, another asleep. Black and red chalk, pen and brown ink on paper, 180 x 204 mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.21 The man on the left is drawing or writing. Can you spot the quill pen in his right hand? The man on the right is fast asleep on a bench. What do you think the man is drawing, or writing about? Why do you think the other man is so tired? They appear to be in a garden under the shade of a tree. But the tree might be a ‘flat’ piece of theatre scenery and they might be actors. There is a join visible above the sleeping figure and around the foot of the seated man. If you look carefully you can see that the drawing of the sleeping man has been cut out from a different sheet and pasted onto the one with the seated man. The two figure studies were made separately. The artist then decided they would make an interesting composition together. It may have been an idea for a painting, or may have been intended as a more finished drawing for sale to a collector. This drawing was sketched in Italy over 400 years ago. We can tell this by the costumes and hats the men are wearing. The artist, Agostino Carracci, was a painter, print maker, tapestry designer and art teacher who lived in Bologna, northern Italy. This sketch shows how good he was at drawing. Pencil lines can be rubbed out, but ink is absorbed by paper and can only be rubbed out by scraping. You have to be very sure to draw in ink! The stamp in the bottom left with a boar and initials ‘T. M. B.’ is the collector’s stamp of Thomas Man Bridge. He owned this drawing in the 19th century and bequeathed it to his sister Frances. She in turn left it to her step-daughter, Mrs Amy Master, who gave it with lots of other art works to Folkestone Museum in memory of Frances

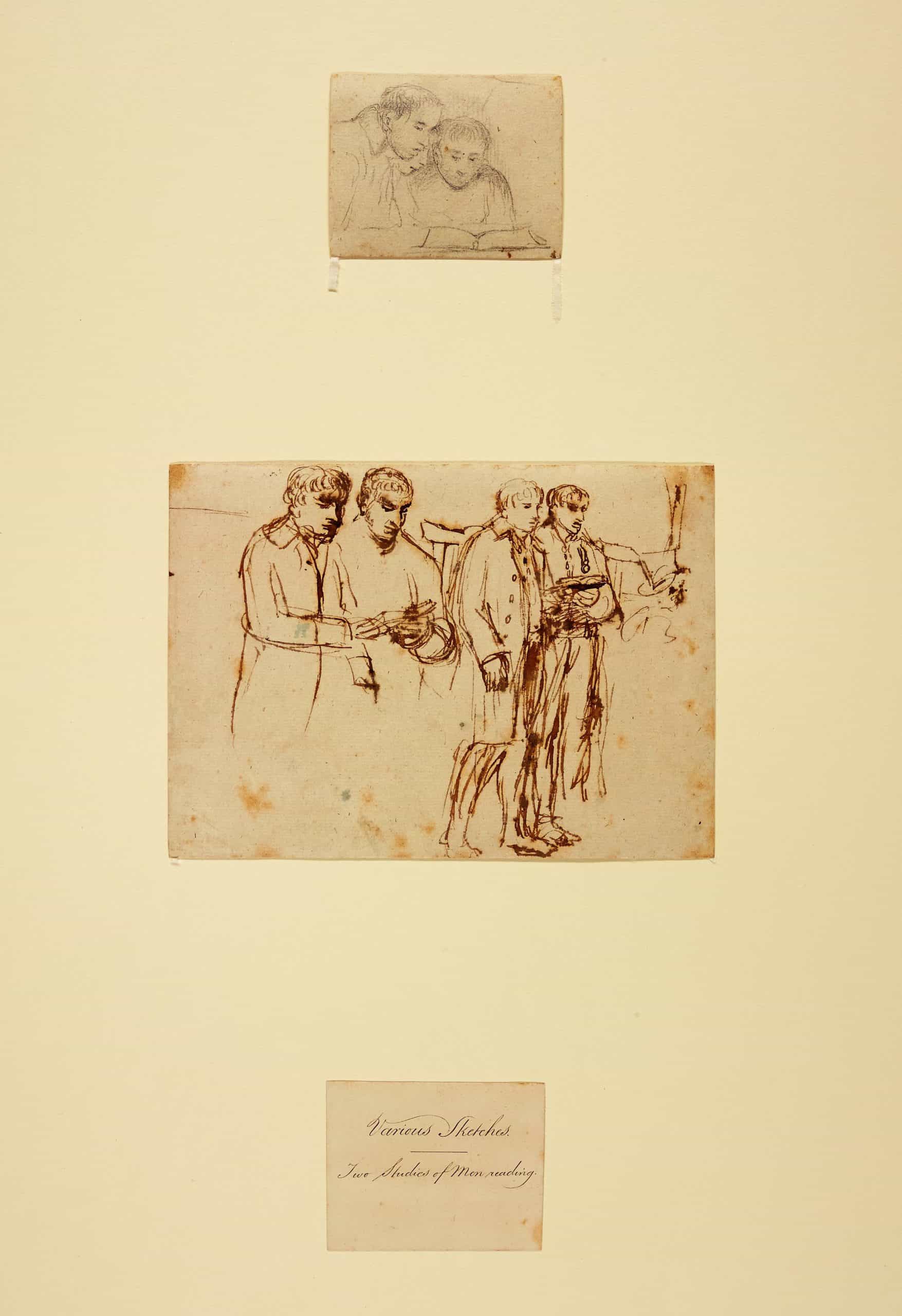

Drawing – Studies of men reading

Sir David Wilkie RA (1785-1841) Studies of men reading Pen and brown ink on paper, 138 x 192 mm; pencil on paper, 65 x 81mm Folkestone Museum (Master Collection) F.3644.68 These men are reading. The standing men are sharing books, holding one between two. They may be prayer books or hymn books; one of the men looks to have an open mouth and may be singing. In the drawing of three heads the men are looking down at a large book. They are probably retired soldiers at the Chelsea Hospital in London. One appears to have a medal pinned to his chest. The Scottish artist, David Wilkie, lived near Chelsea Hospital from December 1810 to July 1811. These drawings are clearly from life and likely date from that time. One of the studies is drawn in pen and ink, the other in pencil. Wilkie’s studies of old soldiers at the Chelsea Hospital gave him the idea for a painting celebrating victory at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He created his most famous painting and masterpiece, Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Despatch in 1822. It is now at the former home of the victor at Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington, at Apsley House, London. The painting shows retired soldiers or ‘pensioners’ at Chelsea Hospital reading the London Gazette, which was the first to print news of victory at Waterloo. Major Henry Percy, aide de camp to the Duke of Wellington, carried the Duke’s personal handwritten account, together with two captured French imperial eagles, from the battlefield at Waterloo, just south of Brussels in Belgium, to London. An Anglo-Dutch army commanded by the Duke, alongside the Prussian army led by Field Marshal von Blucher, had defeated the French imperial army of Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo. Percy travelled straight from the battle on Sunday 18 June 1815 by post chaise to Ostend, where he joined HMS Peruvian. Landing at Broadstairs, Kent, Percy took another post chaise to London, arriving on 21 June. He delivered the Duke’s despatch to the Prime Minister in Grosvenor Square, then went to deliver the news to the Prince Regent in St James’s Square. He presented the captured French eagles to the Prince Regent. There are modern plaques commemorating receipt of the news in both places. Wilkie painted a number of history pictures as well as images of everyday life. They are all packed with detail. He travelled abroad and in 1841 became ill with cholera, a virus for which there was no cure. He died and was buried at sea. His artist friends back in England were devastated. J. M. W. Turner painted Peace, Burial at Sea (Tate Gallery) to commemorate Wilkie.

Passport -Thomas Man Bridge, 1836

British passport of Thomas Man Bridge, dated 1836

Passport – Thomas Man Bridge, Miss Bridge, Miss Bisset, 1839

British passport of Thomas Man Bridge, Miss Bridge, Miss Bisset. dated 1839

Passport – Thomas Man Bridge, Miss Bridge, Miss Bisset. 1843

British passport of Thomas Man Bridge, Miss Bridge, Miss Bisset. dated 1843

Drawing of The so-called Temple of Vesta, Rome

The so-called Temple of Vesta, Rome. Pencil on paper, 264 x 366mm