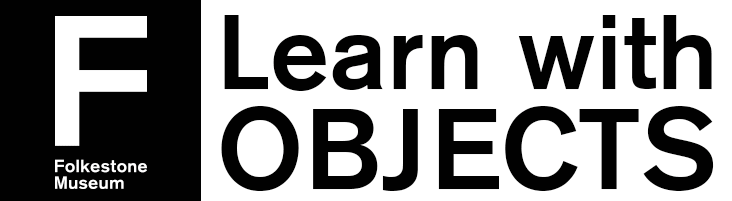

A game to help you learn Mandarin Chinese. The box contains hundreds of squares of printed paper, each with a picture of an object on one side, and the name of it, written in Chinese characters on the other. The game was bought in the village of Tong Shan, China by a British visitor, C D Grimwade, during the First World War in 1915. World War 1 involved people from over 100 countries round the world, and many came to Britain from across the world to fight or to work. Learning other languages was important to help people communicate.

Object: World War 1

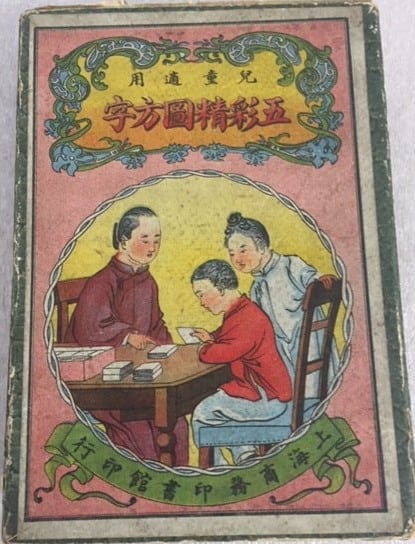

Stereoscopic photos, Gurkha soldiers in WW1

4 stereoscopic photos that shows the lives of Gurkha soldiers on the Western Front in France and Belgium in World War 1. Gurkha soldiers (from Nepal) were one of many nationalities fighting with Britain and her allies in World War 1. They can be recognised by their distinctive slouch hats (wide brimmed felt hats). Gurkhas were incredibly brave soldiers who fought in some of the major campaigns of World War 1 including at the Battle of Loos (where one battalion fought to the last man), Ypres and Gallipoli. Gurkha soldiers still serve in the British Army today and many soldiers and their families have made their home in Folkestone.

Army documents and photos – Charles Willis Theobald

These documents and photographs belonged to Private Charles Willis Theobald, B Company, Royal Canadian Dragoons. Charles was one of thousands of soldiers from Canada who passed through Shorncliffe Camp, Folkestone in WW1 on the way to the Western Front. They include photos of him in Canada and his battlefield will, completed during the Battle of Festubert in 1915.

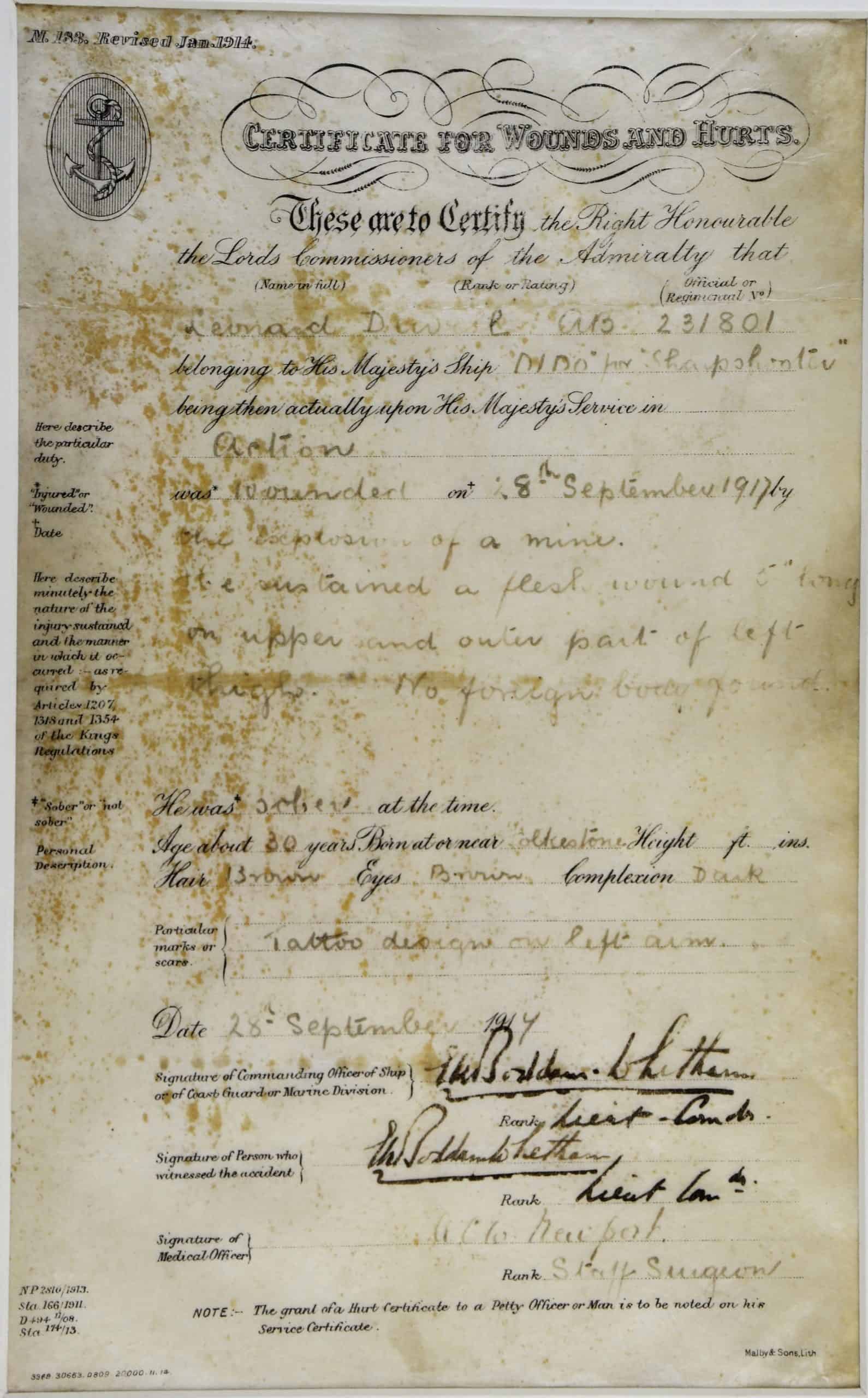

Certificate of Wounds and Hurts – Leonard Drew

Certificate of Wounds and Hurts for Folkestone-born Able Seaman Leonard Drew. He was injured in action on 8 September 1917 by the explosion of a mine while serving on the destroyer HMS Sharpshooter. As a result, he sustained a flesh wound on his thigh 5 inches long. He was brought back to HMS Dido a larger depot ship at Harwich for treatment and assessment. A Certificate of Wounds and Hurts was an official Royal Navy document. It confirmed how and when someone had been injured, and the type and seriousness of the wound. If a seaman had to be discharged from the Royal Navy as a result of an injury, this was a key document that could help him get his pension.

Group photo on the Leas, 1916

Large group photo taken on the Leas, on the Anniversary of the start of the war, Aug 1916. By August 1916 Britain had been at war for 2 years. Hundreds of thousands of British servicemen had been killed and injured, including many from Folkestone. A special service of Intercession was held at Folkestone Parish Church to remember them. Afterwards they marched up onto the Leas for a large group photo. Many of the military and civilian organisations involved in the war effort are represented including the army, the navy, the mayor and town council, together with church leaders and even the Folkestone fire brigade. Seated at the front are the younger generation – army and navy cadets, Scouts and Wolf Cubs (of primary and secondary school age).

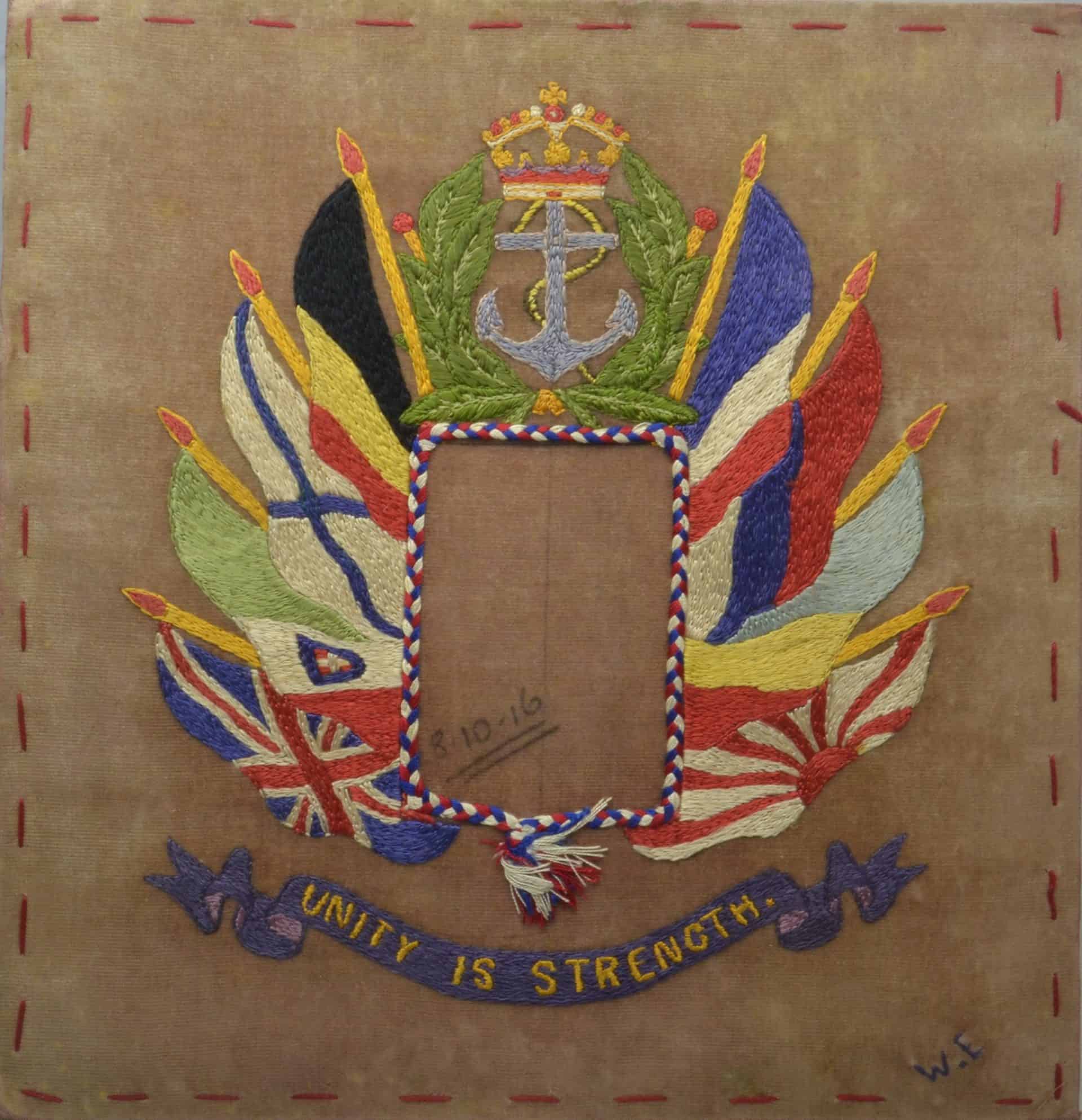

Embroidery – Flags of the allied nations

Embroidery of the flags of all the allied nations fighting alongside Britain in World War 1. The anchor suggests a link with the Royal Navy. Sadly we don’t know who made it, just their initials W. E. and the date, 8 October 1916.

WW1 death penny – George Winter

After the war, the family of every British serviceman and woman killed in World War 1, received a bronze memorial plaque, commonly referred to as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ or ‘Death Penny.’ Over 1 million were issued, made from 450 tons of bronze. No rank was stated on the plaque, because the government wanted no distinction made between the sacrifice of individuals. The figure on the plaque is Britannia holding a trident, standing beside a lion. It was designed by Edward Arthur Preston. Can you find his initials E CR P? They are by the front paw of the lion. This death penny commemorates George Stuart Winter who served in the Canadian Infantry Battalion. He was one of the thousands of Canadian soldiers who were based in and around Folkestone in WW1, before going off to fight on the Western Front.

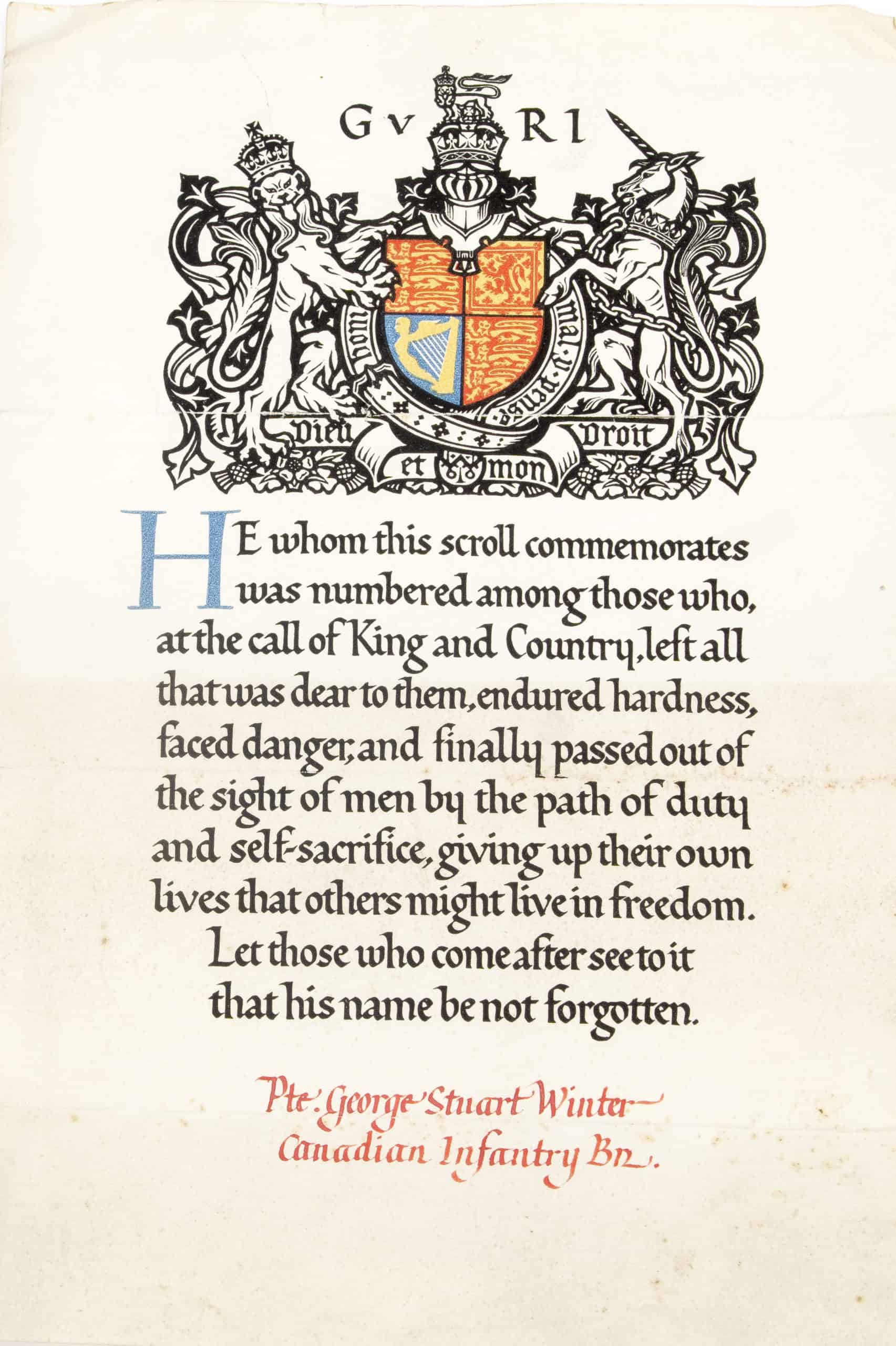

Death scroll – George Winter

WW1 commenmorative death scroll of Private George Stuart Winter, Canadian Infantry Batallion

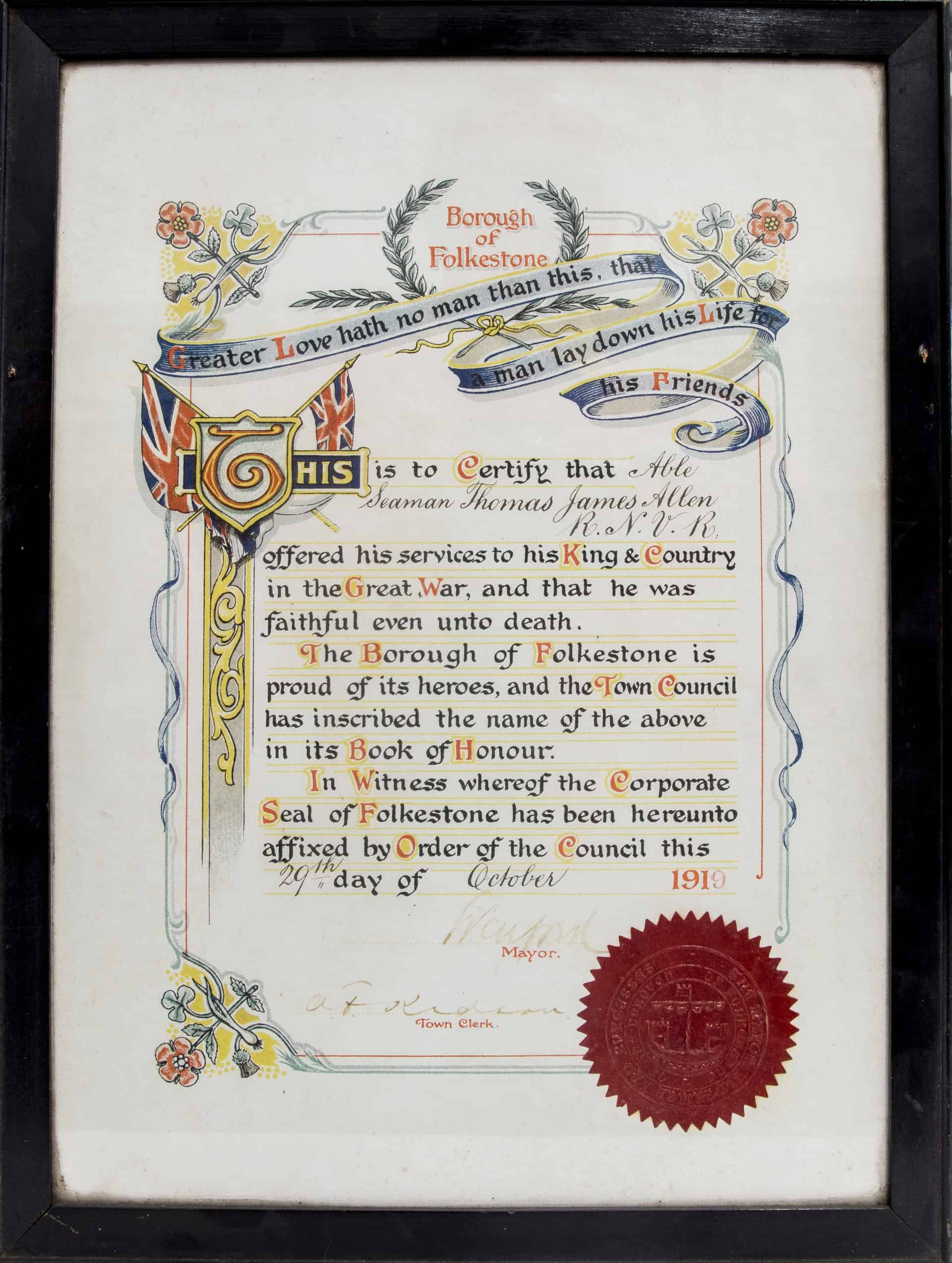

Certificate of Honour – Thomas Allen.

WW1 certificate of honour for Thomas James Allen. It commemorates the life of Able Seaman Thomas James Allen of Folkestone who was killed while serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. His name is inscribed in the Folkestone Book of Honour.

Oil painting – Landing of the Belgium Refugees

Landing of the Belgium Refugees 1914. Oil painting by Belgian refugee Fredo Franzoni. Presented to the town of Folkestone in 1916 in thanks for their kindness to the Belgian refugees who came to the town in 1914. This oil painting shows the arrival of Belgian refugees in Folkestone in the autumn of 1914. Millions of men, women and children were caught up in the fighting in Belgium in the first weeks of World War 1, as the German army overran their towns and cities. Many were injured, or made homeless due to the shelling of their homes, and decided to flee to safety, sometimes with little more than the clothes they were wearing. They came in fishing boats, coalers (coal ships), and anything that could float, as well as on the larger ferries. Homes, food, medical treatment and work were quickly made available to them, and a newspaper Le Franco-Belge de Folkestone set up to help them find missing relatives. The artist was an Italian-born Belgian refugee Fredo Franzoni (1878-1943), who after witnessing German atrocities in his home town of Charleroi, fled to Folkestone with his wife and family in 1914. Already a well-known portrait artist in Belgium, Fredo dedicated 4 months to completing this impressive oil painting, which stands approximately 3 metres wide by 2 metres high. In 1916 it was presented to the town as a thank you for the help and kindness shown to thousands of Belgian refugees by the people of Folkestone. Interestingly, the painting does not recall a specific event. In reality, the refugees arrived in large numbers (over 64,000 refugees passed through Folkestone from August 1914 onwards, and over 16,000 in one day in October 1914), but without such a large and formal welcoming committee. Rather, in the words of the artist it is ‘illustrative in an emblematic manner’ of the warm welcome they received. Fredo was keen to include the faces of many leading Folkestone citizens and those connected in war relief work.

Death Penny – Thomas Allen

After the war, the family of every British serviceman and woman killed in World War 1, received a bronze memorial plaque, commonly referred to as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ or ‘Death Penny.’ Over 1 million were issued, made from 450 tons of bronze. No rank was stated on the plaque, because the government wanted no distinction made between the sacrifice of individuals. The figure on the plaque is Britannia holding a trident, standing beside a lion. It was designed by Edward Arthur Preston. Can you find his initials E CR P? They are by the front paw of the lion. This death penny has been mounted in an impressive silver and beaten copper frame in the form of a cross. It commemorates the life of Able Seaman Thomas James Allen of Folkestone who was killed while serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. His name is inscribed in the Folkestone Book of Honour.

Folkestone Harbour Canteen Books

The Harbour Canteen or Mole café was a small café at the end of the pier, run by dedicated volunteers, including sisters Florence and Margaret Jeffrey and Mrs Napier Sturt. Here soldiers received a friendly welcome, a free cup of tea or coffee, a sandwich or a bun before crossing the channel to France.

The Harbour Canteen Visitor Books are a record of soldiers, Red Cross workers, and notable people who found themselves in the Mole café during WW1.

Victory mug

This is a commemorative Victory mug. It was issued to school children in Folkestone in 1919 after the end of WW1. Included in the picture are the goddess Britannia and a lion, the dove of peace, the flags of all the allied nations (who fought with Britain in the war), a big gun (to represent the army), a ship (to represent the navy) and a plane to represent the air force). When the war ended on 11 November 1918, church bells rang out and street parties were quickly arranged. But relief at the end of the war was tinged with an immense sadness, for all the loved ones who had died and would never return.

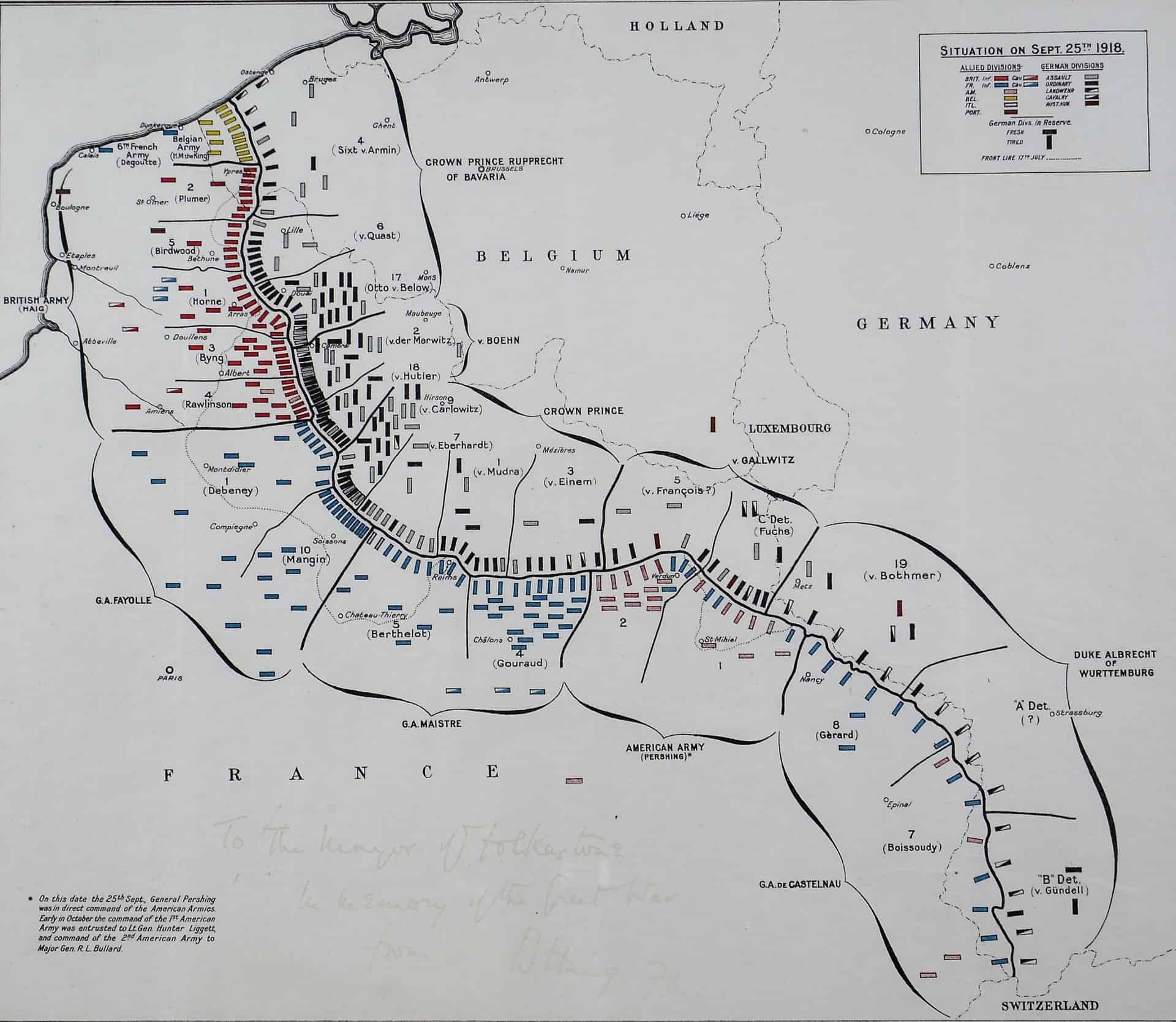

Map of the Western Front

Map of the Western Front signed by Field Marshall Haig, showing the situation on 25 September 1918. The Western Front was a line of trenches from the North Sea to the Alps passing through Northern France and Belgium where British troops did most of their fighting. For most of World War 1 it was a horrendous killing ground, with soldiers attacking each other using rifles, machine guns and high explosive shells. The trenches often filled with thick mud. Millions of soldiers died or were wounded on both sides, including hundreds of young men from the Folkestone area. However, by September 1918, things had changed, and with superior allied numbers, tanks and increased firepower, the Germans were in retreat. Look closely at the map. Can you find the British army units (coloured red) fighting in Belgium (Flanders) and Northern France)? This map is signed by Field Marshall Douglas Haig. The inscription written on the map in faded brown ink reads: To the Mayor of Folkestone. In Memory of The Great War. From D Haig FM.

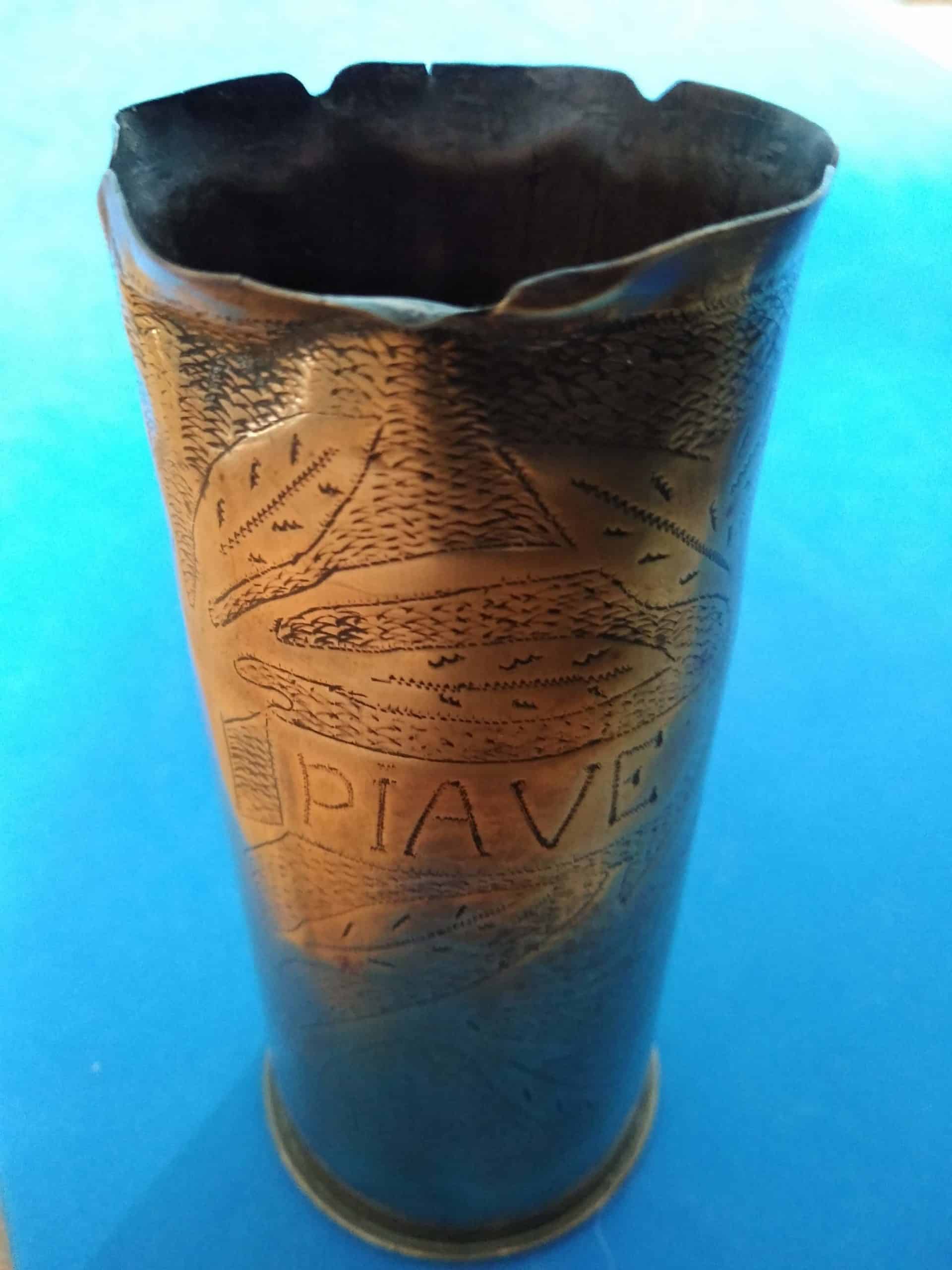

Shell case from Piave

A brass shell case from the Italian Front on the Piave River where Walter Tull fought. It’s been made into a piece of trench art, engraved with the word PIAVE and the leaves and branches of a tree.Soldiers had lots of spare time in the trenches, and those with artistic skills sometimes created pieces of trench art, as souvenirs of the war, using whatever materials they had to hand. Empty shell cases were a favourite item and were made into all manner of useful objects from flower vases and candle holders to umbrella stands!

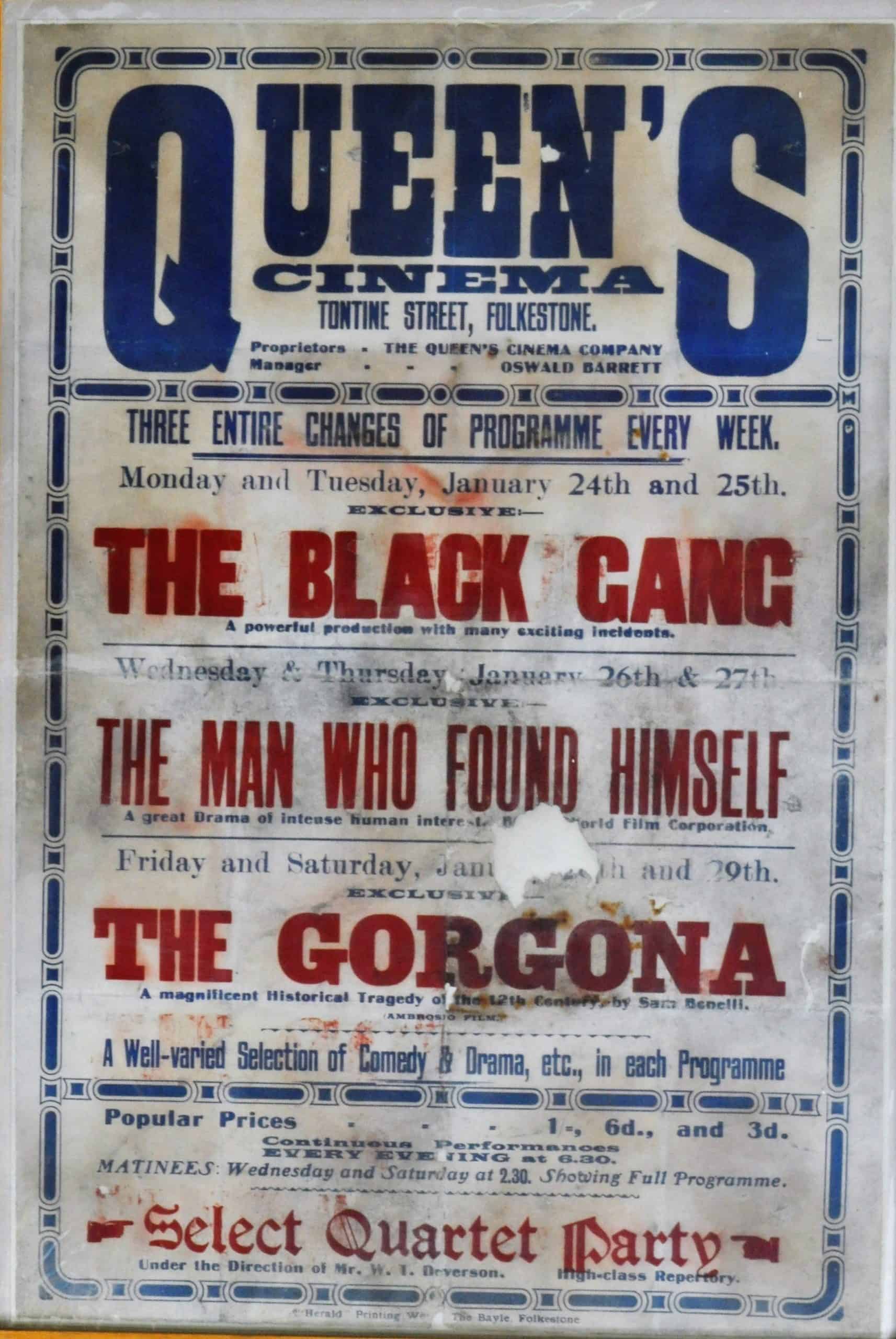

Poster – Queen Cinema, Tontine Street

Poster advertising the Queen Cinema, Tontine Street 1916. Opened in 1912, but badly placed pillars blocked the screen from many seats and it became unpopular. Closed 1917.

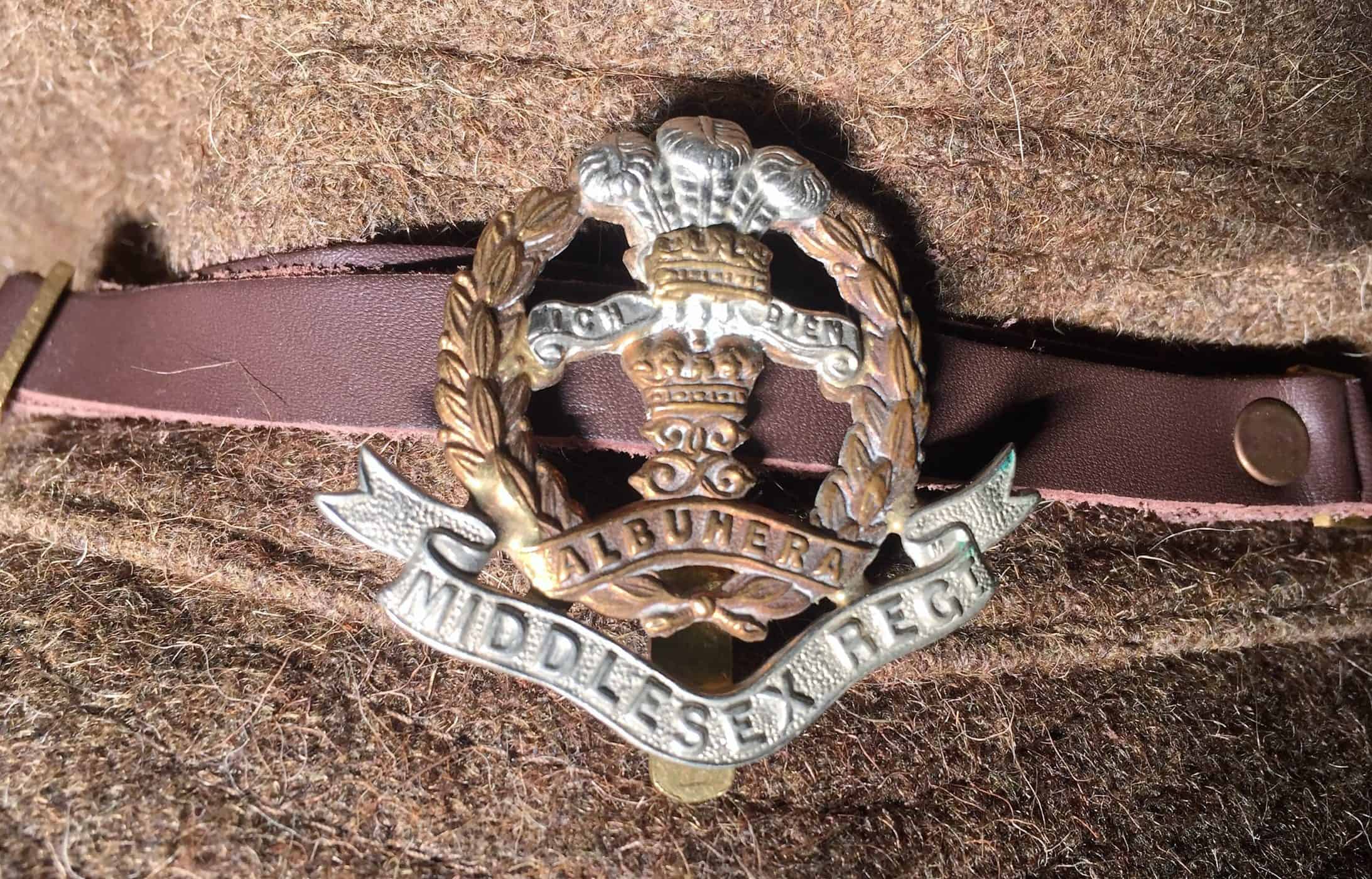

Middlesex Regiment cap badge

Middlesex Regiment cap badge. The same kind of badge that was worn by Walter Tull.

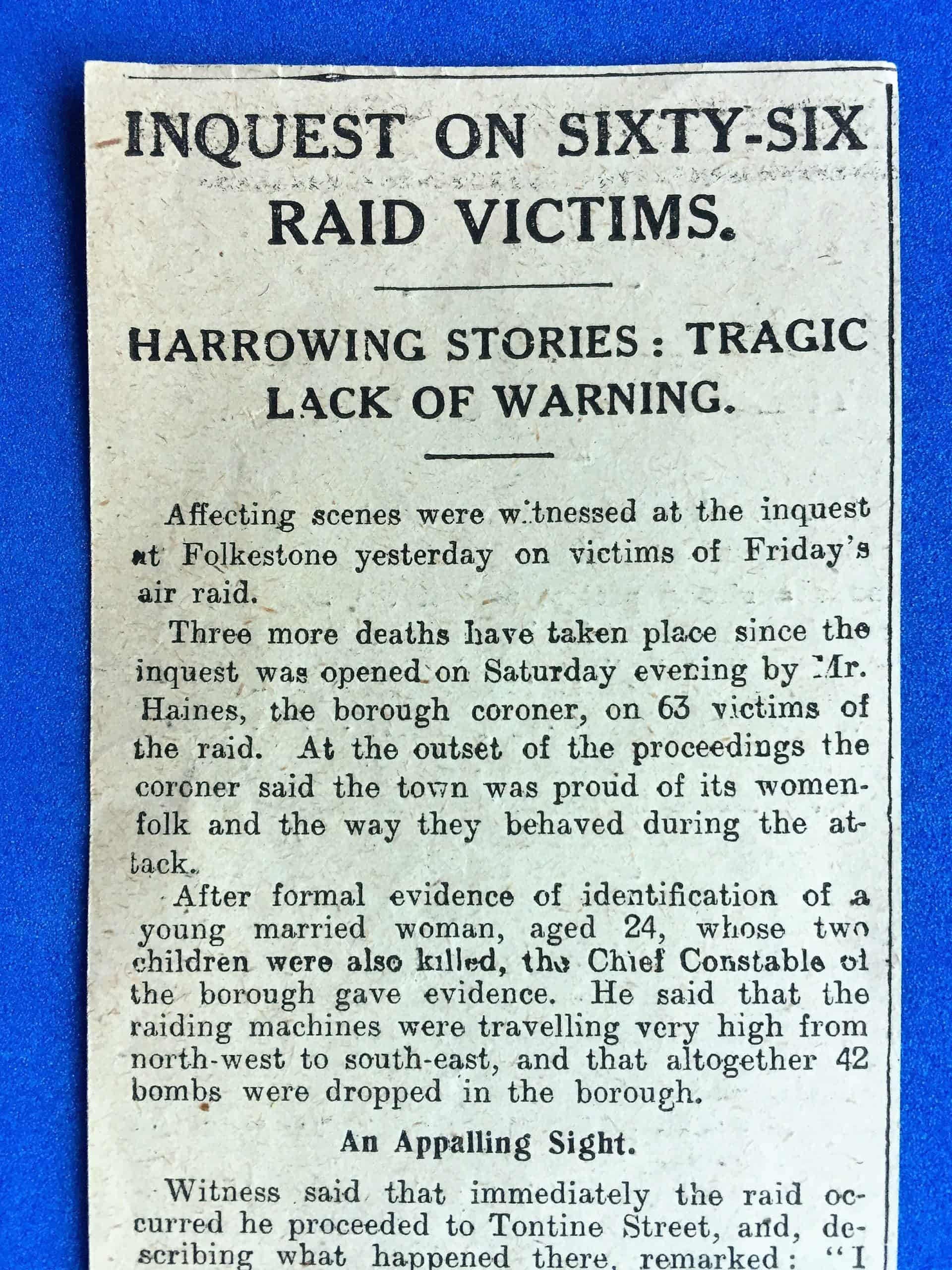

Newspaper cutting – Tontine Street inquest

. Newspaper cutting. An account of the inquest into the Tontine Street bombing, 1917. From a local newspaper, possibly the Folkestone Herald. 1917.

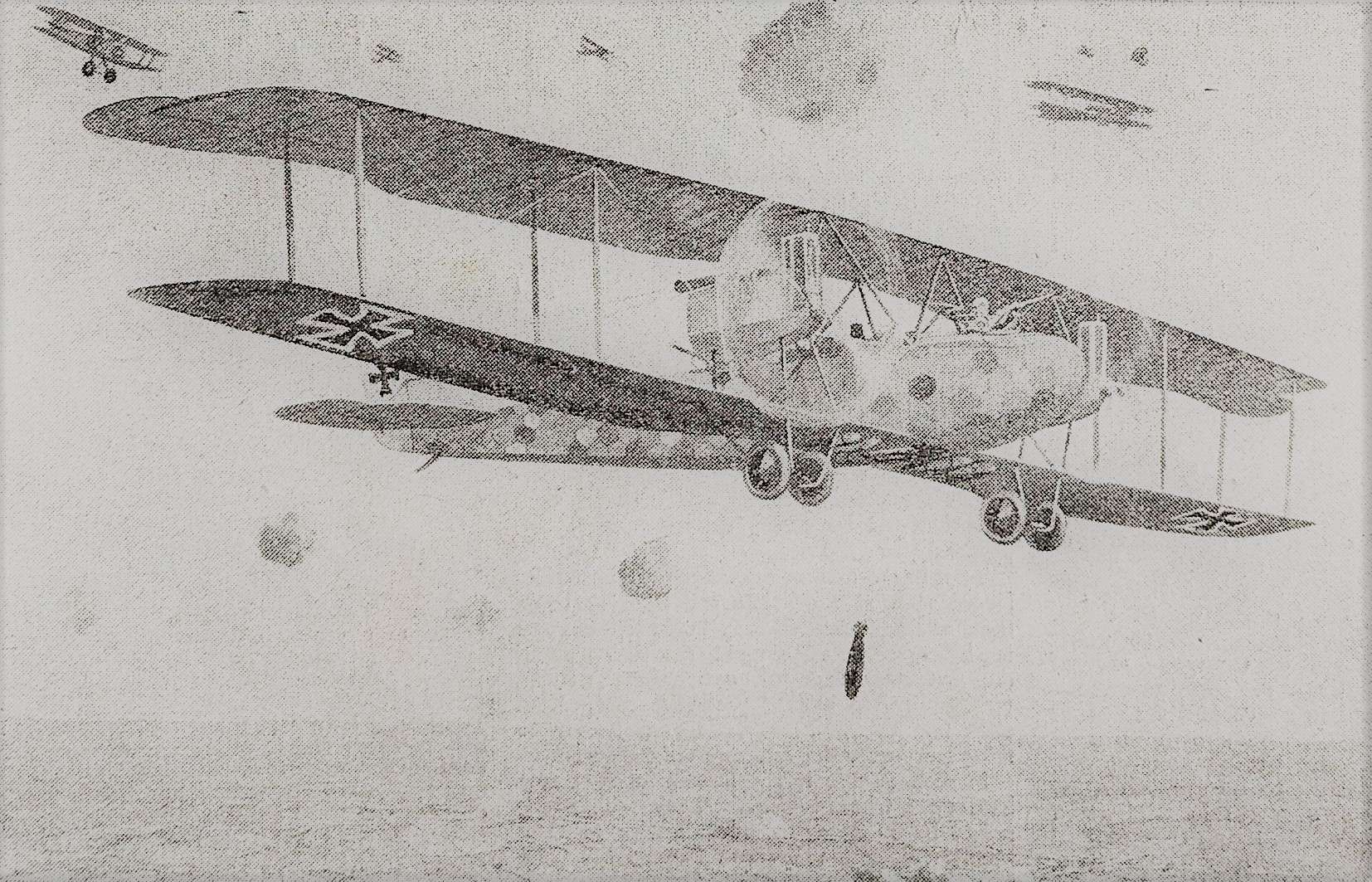

Magazine cutting – Gotha bomber

Page from War Illustrated 1917. Aircraft pictured and described. Feature on Gotha bomber with illustration of plane.

Memorial plaque – Tontine Street bombing

Memorial Plaque to the Tontine Street bombing. This was attached to a Tontine Street lamp post for many years, close to the spot where the bomb exploded.

WW1 penny flags

These tiny cardboard flags (about 2 to 3cm long) were presented to people who donated money to charities at special Flag Days during World War 1.The charity flags shown here are: The Belgian Refugees Relief Fund, King Albert’s Army (to raise money for Belgian soldiers),The Salvation Army Ambulance Unit (which operated ambulances on the Western Front), Dr Barnardo’s Homes (for orphaned children) and an unknown charity for soldiers’ children. Flag days were an exciting new way of raising money and the idea spread like wildfire. Very soon there were flag days being organised in towns and cities across the UK, including Folkestone. Volunteers stood in the street with collecting tins, asking passers-by for a donation. In return they got a flag to pin to their lapel. Many people kept the flags as souvenirs and some pinned or glued them into scrap books.

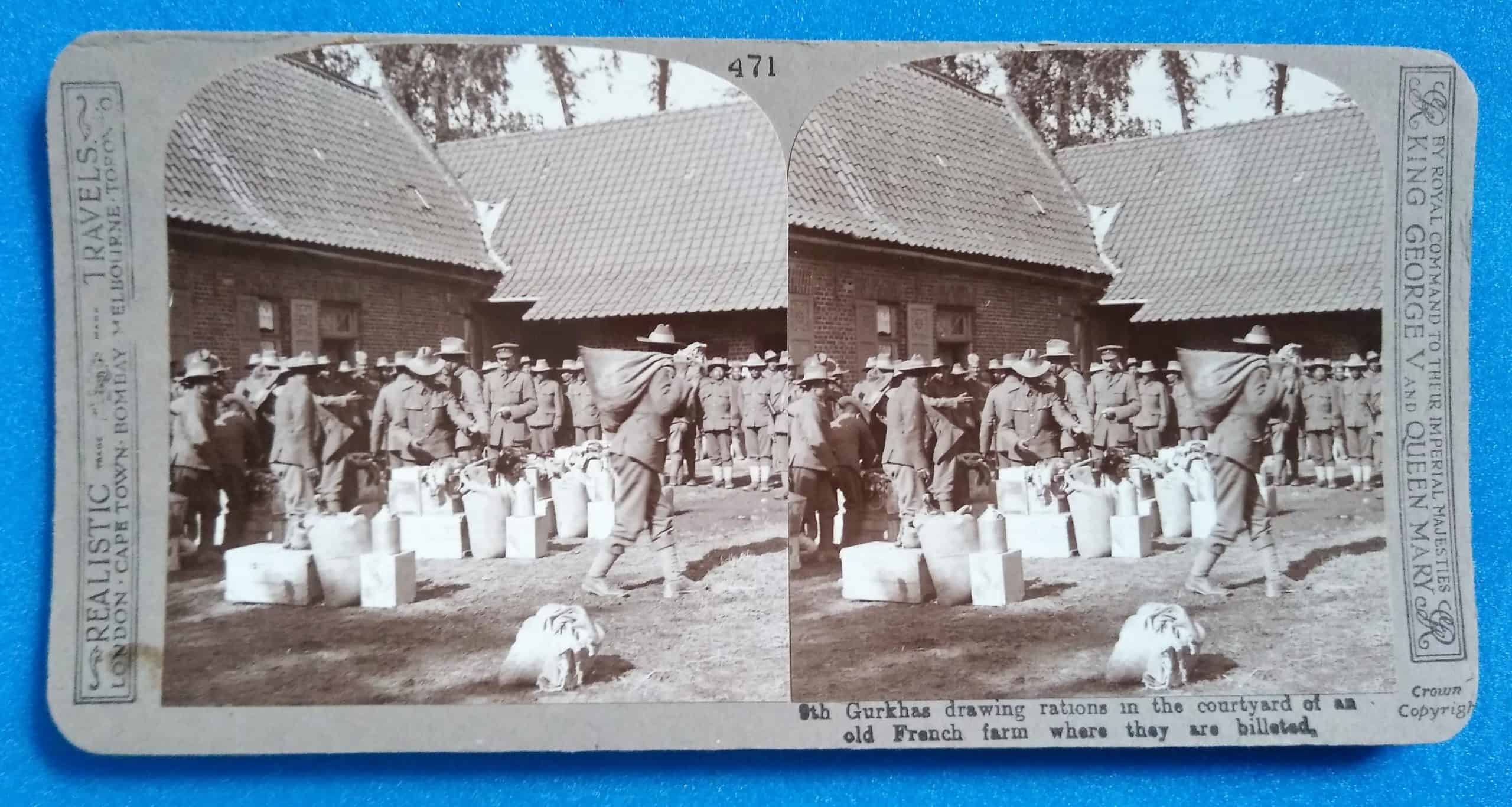

Lapel badge of RMS Laurentic

A brass and enamel lapel badge of a ship called RMS Laurentic. The design is in the shape of a ship’s wheel. RMS Laurentic was built in 1908 for the White Star Line (whose flag is also on the badge) and before World War 1 carried thousands of passengers across the Atlantic to the USA and Canada. On the outbreak of World War 1, RMS Laurentic was converted into a troopship, and brought thousands of Canadian soldiers to the UK. In January 1917 she was sunk by a mine off Ireland (which had been laid by a German U-boat) and sank within an hour with the loss of 354 lives including Chief Petty Officer Charles Albert Taylor, age 24, a member of the Royal Navy crew, who lived in Folkestone.